by Jeff Dooling, Andre Dupuis, Scott Jones, James Peck and Neven Vincic

Most Canadians have little appreciation of our profound daily dependence on space systems. We are ill-prepared to meet the challenges and seize the opportunities presented by today’s complex space domain and without nationally focused space governance, the essential opportunities for Canada to be a valued contributor might never be fully realized.

This article is based on a Department of National Defence (DND) Mobilizing Insights in Defence and Security (MINDS) Expert Briefing Series paper which explores Canada’s critical dependencies on space-based systems and highlights the lack of a comprehensive, co-ordinated, and fully supported national plan for advancing Canadian space capabilities. Canada’s space capabilities, although strong in a number of niche areas, are siloed by a lack of synergy between departmental objectives. An overarching national vision for the future of Canada’s use of space-based capabilities that encompasses civil, commercial, and national security/defence needs has never been articulated. Canada needs a nationally focused framework for space governance, and equally as importantly, a fully supported plan that enables the vision. Canada’s allies and competitors are seizing the space agenda with new national space policies and strategies, while Canadian government departments compete to fund their own internally focused mandates, absent a unifying vision.

Space – Out of Sight and Out of Mind

Canada is wholly reliant on space-based systems for a wide range of critical daily activities. Space connects us, enables business to function and helps move people, goods, and information, all on a global scale. The internet, cellphones, and navigation, to name just a few, are all enabled by space-based technologies, yet that fact is obscure to most.

What would happen if Canada lost its access to, or use of, satellites? GPS navigation systems would be unavailable. Clocks would not synchronize to a universal standard time. Cellphones would lose signals and internet connections would instantly drop. Bank cards would no longer function, while debit payments and access to cash would be impacted as ATMs went offline. Stores could no longer conduct financial transactions. Businesses would close. Traffic lights, reliant on GPS timing signal synchronization for proper functioning, would falter, causing chaos on the roads. Similarly, electrical grids would lose timing synchronization, resulting in widespread rolling blackouts. Security systems would fail as a result of power loss and many critical national defence communications and operational systems would cease to function. Imagine if this were to happen just for one day? Imagine a week? Imagine the cost and resulting chaos and panic.1

Canadians need to be better informed about the prominence of space-based technologies in their lives, the importance of accessible space infrastructure and the benefits of a viable and robust Canadian space industry. Typically, when something is out of sight, it is also out of mind, and there is no more striking example than satellites in space. An absence of space-mindedness by the general public results in a significant lack of awareness about the critical importance of space-based systems to modern life. Such lack of understanding is dangerous as we continue to increase our space dependencies without consideration of the vulnerabilities surrounding these systems, and the various actors that have capabilities to disrupt them. A well-informed public often leads to better understanding, increased support, and greater acceptance for government spending on expensive investments.

Current Assessment – Risks, Threats, Seams, and Gaps

Canada is a proponent of the use of space as one of five internationally agreed-upon global commons (high seas, deep seabed, atmosphere, Antarctica and space), treating it as a shared environment with freedom of access for all. Yet access to and freedom to operate in space has changed dramatically in the past 20 years. Our adversaries, and many of our allies, have accepted that space is no longer a sanctuary. India, China, Russia and the United States have all developed the capacity to attack space systems, while many other nations have developed the ability to interfere with ground elements of space systems, through cyber/electronic means or kinetic attack. Space has the potential to become a future combat environment, putting the civil, commercial, and national security advantages we enjoy from it at risk.

As a middle space power, Canada relies very heavily on military allies, civil and commercial partnerships and multi-use systems to achieve required space effects.2 The awkward reality is that we own and operate very little of what we actually need and use on a daily basis. We are dependent on others for critical capabilities. Those capabilities we do own and operate, such as the Canadian multi-use Radarsat series of satellites, provide critical government, commercial and military space effects. But across the range of civil, commercial, and national security space activities, all closely interlocked at the working level, Canada has no all-encompassing national space policy, strategy or plan to ensure those activities are aligned in a whole-of-government effort, or that they represent the best overall collection of capabilities for Canada.

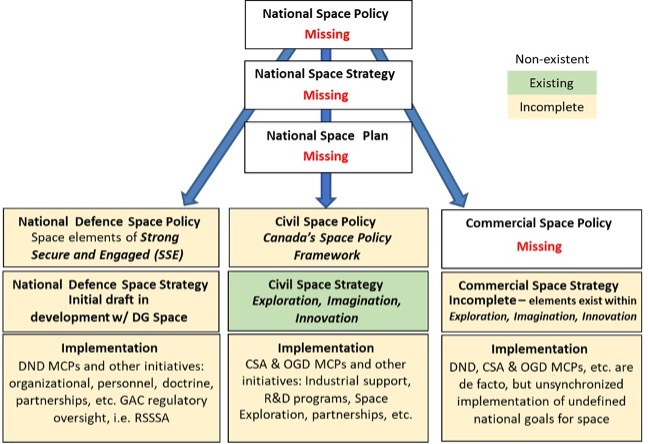

Instead, as Figure 1 shows, Canada has an incomplete collection of civil, commercial and defence space policies, strategies, and initiatives, exposing serious gaps and seams in policy and planning.

For example:

- The Radarsat series of capabilities have evolved through a variety of ownership models (public-private partnership, commercial ownership, government ownership). Regarding RADARSAT-2, such changes had serious problematic impacts on the defence crown jewel of Canada-U.S. intelligence sharing;

- Overlapping and competing projects such as DND’s Defence Enhanced Surveillance from Space project (DESSP) and the Canadian Space Agency’s (CSA) Earth Observations Service Continuity (EOSC) project, both designed to replace existing Radarsat systems, lack national guidance to harmonize competing goals, leading to wasted resources and duplicated costs;

- National security oversight of Canadian remote sensing space systems by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) via the Remote Sensing Space Systems Act (RSSSA)3 hinders the development of the Canadian remote sensing space industry and limits its contributions to Canada’s vision for space; and

- Tensions between space as a military operational domain (e.g., military space doctrine) and diplomatic initiatives for international space governance (e.g., Canada’s inputs to UN Resolution 75/36 on “Reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors” (2020)) require overarching guidance to work in harmony with one another and conform to a focused policy.

Such gaps and seams lead to inefficiencies, which will continue to impede the implementation of Canada’s full range of space initiatives unless an overarching, harmonizing national vision for space is established. Such a vision must include a viable, well considered and co-ordinated allocation of roles, responsibilities and resources. As discussed below, a review of some of our closest allies’ approaches provides some guidance on what Canada’s vision for space should include, namely:

- Effective national leadership, potentially including a cabinet committee for space,4 chaired by the prime minister, to ensure broad engagement and optimal allocation of funding for implementation of departments’ desired projects;

- A national space policy to identify and describe Canada’s goals for space that considers, at a minimum, partnerships, niche contributions, economic opportunities, required sovereign capabilities and leadership objectives in global space governance;

- A national space strategy to describe how Canada’s goals for space will be achieved, including the co-ordinated allocation of roles and responsibilities for space activities to departments and agencies, and guidance for subordinate civil, commercial and national security space policies and strategies; and

- Most critically, a fully considered and funded plan that enables the execution of the strategy; without the necessary centralized funding, strategies become words without outcomes.

Canada’s Space Niches

Canada’s space industry has leaders in a number of niche fields: space-based SAR, robotics (the Canadarm), SATCOM (Telesat/Kepler) and remote health care, to name but a few. It is clear that Canada has an excellent pedigree in space capability, and many opportunities for further development. We should begin by looking at what we already do well for future investment, and then reassess, verify and update our vision based on changes to the market and our current and future needs. We should strive to expand our expertise in our strengths, with the aim of developing these into world-class capabilities. There are in fact already some key areas where Canada can focus its developmental attention, effort, and resources:

- As one of a handful of three-ocean nations, Canada should further develop and expand our space-based maritime domain awareness capability to one that provides global coverage in real time and integrates elements of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML);

- Develop state-of-the art replacements for space-based situational awareness systems, which should leverage the excellence of our Sapphire (surveillance of space satellite) project to create similar yet advanced capabilities;

- Actively invest in our civil space and astronaut program and support industry, as they lean into the Lunar Gateway initiative;

- Encourage and facilitate the merging of government, civil and commercial space operations to enable effective partnerships and resource sharing.

Comparative Approaches: Critical Internal and External Capability Linkages

In our current state, Canadian space capabilities are siloed and generally independent of each other. Within DND, the need to consolidate capabilities, force generate space expertise, develop effective, affordable, and timely systems, and employ those capabilities as a system of systems has never been more important.

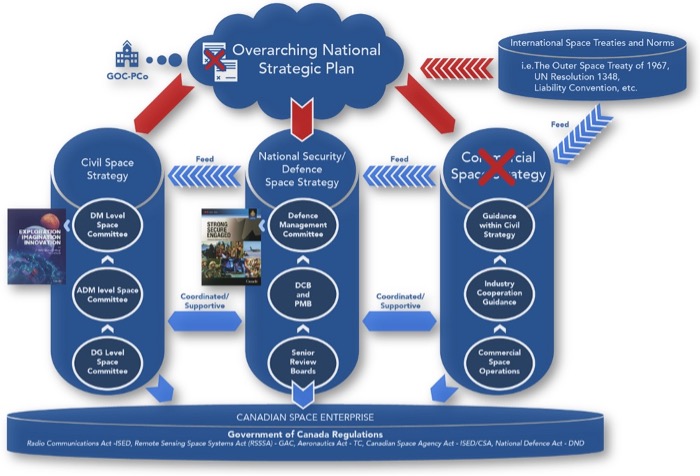

As seen in Figure 2, current direction and guidance are not harmonized and are moving forward without an overarching and collective vision. CSA focuses on shared and open architectures whereas security concerns within defence point more often to classified requirements. A national space strategy will enable a harmonized, resilient and mutually supportive Canadian space enterprise, with a shared understanding of need, shared operations (where appropriate) and shared situational awareness. As depicted in Figure 3, these aspirations will only mature if they are born from a shared vision and a clear plan.

We are not the first nation to recognize the urgency of our situation. Some of Canada’s close allies have recently addressed very similar issues.

United Kingdom

The 2021 National Space Strategy outlines the U.K. government’s civil and defence ambitions and goals in exploiting space and space systems and represents a centralized intergovernmental approach to achieving national objectives. It examines the benefits, strengths, opportunities, and threats to the U.K.’s existing and emerging space sector and systems. Key points include the need for significant private sector investment in space activities, and the changing role of government from primarily a funder to an active (and influential) customer of space systems and services. The Strategy refers to an “own, collaborate or access” framework based on assessments of what capabilities must be owned on a sovereign basis, which can be secured via collaboration with partners and allies and those that can be accessed through the commercial sector.

The subsequent 2022 Defence Space Strategy: Operationalising the Space Domain outlines a vision for how the Ministry of Defence will fulfil the stated goal to protect and defend the U.K.’s national interests in and through space. It discusses the U.K.’s reliance on space systems for critical civil, commercial and national security services and speaks to the increasingly competitive, hazardous and potentially threatening character of space as an operational domain. Significant emphasis is placed on the need to preserve strategic advantage in space through interoperability and burden-sharing in support of allied efforts in space, including preventing conflict, deterring escalation, optimizing resource usage and enhancing mission assurance.

Australia

In 2018, the newly created Australian Space Agency released a robust civil space strategy, Advancing Space: Australian Civil Space Strategy 2019-2028. The strategy outlines a staged plan of meeting the government’s economic goals in the space sector. It aims to triple the size of the Australian space sector and create up to 20,000 jobs by 2030, while targeting dual-use capabilities that could be leveraged across government.

In mid-March of 2022, the Australian Department of Defence (DoD) released Australia’s Defence Space Strategy, which describes the strategic context of the space environment and articulates a set of objectives to realize a vision of Australia as an integrated space power by 2040. The Strategy identifies five lines of effort broadly intended to assure access to space; integrate delivery of military effects across the whole of government; increase national understanding of critical space dependencies; pursue sovereign space capabilities and develop a national space enterprise; and facilitate sustainable and effective use of the space domain. Similar to Canada, Australia’s competitive advantage and sovereign capabilities in space domain awareness could contribute to burden-sharing in multilateral efforts, reducing dependence, retaining relevance and ensuring interoperability.

United States

The 2020 National Space Policy of the United States of America presents a unified intergovernmental approach, including guiding principles, goals, cross-sector and sector-specific directives as they relate to civil, commercial and national security elements of U.S. space policy. The 2020 U.S. Defense Space Strategy Summary, building upon the established national security sector guidelines and in recognition of a global security environment characterized by renewed great-power competition, seeks to enable the DoD to achieve its desired conditions in space. While the U.S. case represents ambitions and efforts beyond Canada’s reach, it does provide an effective template of a comprehensive nation-wide approach to articulating and realizing the importance of space and access to it.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that Canadian society is critically dependent on space-based systems for an increasingly wide range of daily activities. It is also clear that space-based systems are vulnerable to disruption, degradation, and destruction, whether by an accidental collision in space or by deliberate targeting of space-based systems.

Although most nations can increasingly access space systems, large, complex projects are too expensive for most nations to go it alone. However, interoperability and burden-sharing initiatives among partners and allies enable nations to concentrate investment on developing niche capabilities. Canada is known today for excellence in certain space-based technologies while new niche competencies may be realized when the Canadian space enterprise, consisting of civil, commercial, and national security activities, is finally harmonized.

Creating a carefully considered and well-connected Canadian space enterprise requires overarching national governance and direction. If a clear vision, strategy, and policy are articulated, funding will follow and breathe life into the words of Strong, Secure, Engaged for defence and Exploration, Imagination, Innovation for civil space. It will, for the first time, provide focus for the Canadian space industry and result in a much more co-ordinated approach to achieving the initiatives currently identified in departmentally focused space strategies.

End Notes

1 Anusuya Datta, “Modern Civilization Would Be Lost Without GPS,” Space News, August 3, 2021, https://spacenews.com/modern-civilization-would-be-lost-without-gps/. “This 2019 report sponsored by the National Institute of Standards and Technology estimated the loss of GPS would cost the U.S. economy $1 billion a day, or $1.5 billion if the technology failed in the April-May planting season for farmers.”

2 Related to the notion of dual-use technology applications, in this context multi-use refers to the end uses of space systems, classified as civil, commercial and/or national security.

3 Space Strategies Consulting Ltd. (SSCL), “2022 Independent Review of the Remote Sensing Space Systems Act (RSSSA),” Parliament of Canada, House of Commons, Sessional Paper No. 8560-441-1062-01, Tabled March 21, 2022, 2022 Independent Review of the Remote Sensing Space Systems Act (RSSSA) (international.gc.ca).

4 Similar to the national space councils recently established in the United States and United Kingdom.

Space Strategies Consulting Limited (SSCL) is a team of space professionals seeking to bring clients a deep understanding of the complexities of space operations across the entire spectrum of users from commercial, civil, and national security stakeholders. The organization’s mission is to bring forward innovative solutions and disruptive capabilities for the most pressing challenges in aerospace, near-space, and space domains for various applications. www.sscl.solutions

Reprinted with permission, The Canadian Global Affairs Institute, June 2022

Link to original article.