In April 2023, at the annual Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries (CADSI) Navy OUTLOOK, the Navy briefed the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP) and what they considered were the key attributes for a future submarine to replace the in-service Victoria-class submarines. Unsurprisingly, the brief called for diesel electric submarine, fitted with a non-nuclear air independent propulsion (AIP) system; clearly stating nuclear power was not an option.

The brief then listed a number of key requirements, notably the need for significant “Range, Endurance, Persistence”, which they defined as the ability to deploy undetected out to a range of 3500 nautical miles (nm), patrol covertly for 21 days and return home undetected.[1] A substantial requirement that heretofore has been the domain of nuclear power. To achieve this capability, in a non-nuclear powered submarine, demands the submarine have the ability to conduct a ‘snort transit’ to and from its patrol area, as submarines simply cannot carry enough fuel for the fitted AIP system, particularly liquid oxygen, to conduct a deployment of this magnitude.[2]

Range, Endurance, Persistence

The definition of range is relatively easy to calculate, however, it is the definition of overall endurance, as it applies to submarine operations, that warrants a closer look.

- Range can be defined as: “the distance that can be covered by a vehicle without refuelling”.

- Endurance can be defined as: “the ability to continue doing something difficult for a long period of time”.

- Persistence can be defined as: “continuing to try to do something despite difficulties, especially when others are against you”.

These definitions neatly sum up the essence of a future Canadian submarine capability: a submarine that can transit long distances, which are defined by geography and mission, then operate covertly, in a potentially hostile environment, for a protracted period of time, and then return home without external replenishment or support.

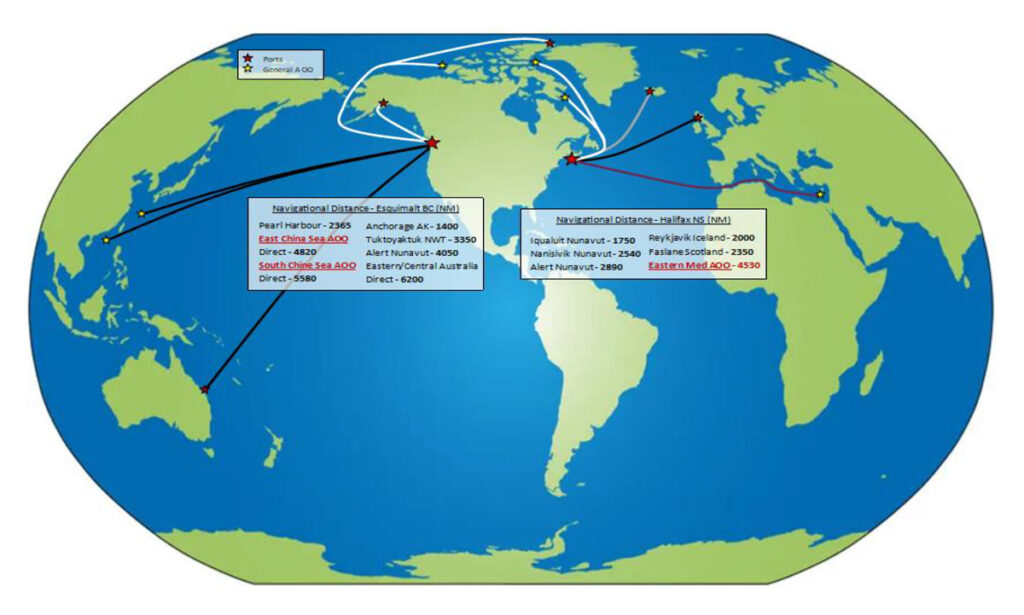

One may ask why endurance is so important to Canada, and why is it different, compared with many other allied submarine navies? Simply put it is all about geography and the threat, specifically:

- In the defence of Canada, it is the enormous distances from support bases, in Halifax and Esquimalt, to future defensive patrol areas – especially the Arctic.

- In support of allies, it is the vast ocean expanses which are defined by future adversaries – notably in the Asia-Pacific.

As Canada has been continuously operating submarines for over sixty years, one may ask what has changed? The short answer is the international situation – with the fall of the Soviet Union at the end of the 20th century and the rise of an increasing disruptive and aggressive China in the 21st century, the geo-political threat has decisively shifted to the Asia-Pacific from the Euro-Atlantic.

Throughout the Cold War Canadian submarines routinely deployed to, and then operated in, the eastern Atlantic (EASTLANT) and the maritime choke points of the GIUK gap.[3] Today the focus has shifted to the Asia-Pacific and the Canadian Arctic, which involve significantly greater transit distances without external support close at hand. It is noteworthy that Canada’s current fleet of Victoria-class submarines were originally designed and built for the British Royal Navy (as the Upholder-class) to transit from the Clyde submarine base in Scotland to the GIUK gap, patrol for three weeks and return. These submarines were never intended for the endurance that Canada required and were only acquired as a stopgap submarine capability extension until such time as a replacement submarine was obtained.

Understanding that a Canadian submarine will need the endurance normally associated with larger nuclear-powered submarines, but in a conventional submarine design, what then are the limiting factors that define conventional submarine endurance? These can be broken down into a number of subsets, as follows:

- Fuel – to meet anticipated future missions, the submarine must carry enough fuel for power generation for both propulsion and onboard services.[4] This is not just fuel for diesel generators, it also includes any specific fuel for fitted air-independent-propulsion (AIP) systems, which necessarily includes liquid oxygen.

- People – while submarine crews are typically smaller in number than comparable surface warships, habitability and adequate food storage will limit effective persistence during lengthy patrols. Using the definition of transit and patrol capability provided by the RCN, this translates into a minimum of seven weeks at sea with the ability to extend the time at sea further. Moreover, unlike the surface navy, there is no replenishment at sea – you sail with what you have onboard. Thus, food in a submarine becomes more than simple nourishment, mealtimes break up the monotony of a patrol and are critical to good morale and fighting efficiency. As fresh food typically does not last more than two weeks, everything else must be stored according to pre-prepared menu plans, mainly in freezers.

- Waste – people also produce waste and environmental regulations, particularly the MARPOL Polar Code when operating within 12 nautical miles of any ice shelf or fast ice, demand that sufficient onboard waste storage be incorporated into the design.[5]

These three factors alone drive the size of the submarine, with Canada’s requirements demanding a larger submarine design then those historically operated by European submarine manufacturers where Canada has historically looked to for submarines. Moreover, open-ocean operations require different sea-keeping characteristics than a submarine that is designed to operate in shallower waters of the Baltic, North and Mediterranean seas.

In addition to size, there are other factors that determine endurance, specifically the maintenance schedule of the submarine and how it is maintained in practice. Once a submarine deploys its ability to conduct defect repair is severely limited, therefore, the material condition of the submarine is critical to mission achievement. To do this, the supporting infrastructure must be in tune with the designed maintenance philosophy – whilst being adequately supported logistically, so that maintenance schedules are met without inordinate delays impacting submarine availability.[6] Pushing a poorly or inadequately maintained submarine to a high operations tempo will invariably result in limitations of the crew to meet endurance expectations. Furthermore, operating orphan fleets, that are not in service with another navy, further restricts maintenance efficiency, as a common supply chain and platform information sharing can significantly enhance technical support activities. In short, the submarine must be technically reliable, which is a reflection of both design and maintenance support activities, particularly supply chain.

Once deployed on operations, endurance can also be measured tactically, in the limitations of the fitted systems. In a conventional submarine life completely revolves around power generation and storage – the battery. A diesel-electric submarine (including those fitted with AIP) run diesel generators, while snorting, to recharge the battery, which is then used for both propulsion and domestic services – known as the ‘hotel load’. While modern AIP systems allow for the ability to generate power without snorting, they are all limited by the amount of liquid oxygen carried onboard, which typically reflects less than three weeks of operation. This is fine for nations that operate their submarines close to home with access to resupply, but for Canada a lengthy transit to a distant patrol area is a fact of life.

A lengthy “snort transit” to an assigned patrol area is the reality of Canadian submarine operations and how often the battery needs charging is dependent upon the mission specifics, transit speed and other electrical power demands of the submarine. Because lengthy transit distances necessarily require a higher speed of advance than when patrolling in a defined area, the battery must be frequently recharged. Moreover, when snorting, the submarine must operate at periscope depth with a number of masts raised, thus risking detection. Consequently, all efforts must be made to reduce the amount of time needed to snort, which is dependent on the ability to rapidly generate electricity and efficiently store it.[7]

Finally, Canada has indicated that it wants a submarine with sufficient endurance to patrol covertly for three weeks before the return transit home. Current AIP technology offers the ability to meet this requirement without snorting, but it is limited by the amount of fuel required by the fitted AIP system that can be carried. Again, the bigger the submarine the greater amount of fuel that can be carried, but conversely it also means the greater amount of power that is required to propel a larger submarine which impacts the subsequent power draw on the battery. That said, once in its assigned patrol area, a conventional submarine normally operates at very slow speeds to maximize battery life as well as reducing radiated noise for acoustic advantage when conducting passive sonar searches.

In summary, to meet anticipated future 21st century geo-political threats, Canada’s future submarine, must be designed with the endurance critical to meeting national requirements, which necessarily includes range and the ability to persistently patrol “up-threat” for extended periods. This is significantly different from most navies operating conventional submarines today.

References

[1] Department of National Defence, CADSI OUTLOOK 2023 Canadian Patrol Submarine Project brief, April 2023.

[2] A ‘snort transit’ is when the submarine operates its diesel generators by snorting (snorkeling), at periscope depth, to charge the battery while transiting to its patrol area.

[3] GIUK Gap – Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom the gap that separates the Norwegian Sea and the North Sea from the open Atlantic Ocean. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GIUK_gap accessed 20 September 2023.

[4] Typically referred to as the “hotel load” a submarine must have sufficient power for atmosphere maintenance (breathable air), weapons and sensors, cooling and food storage and preparation.

[5] IMO Polar Code at https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/safety/pages/polar-code.aspx#:~:text=The%20Polar%20Code%20covers%20the,waters%20surrounding%20the%20two%20poles and https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Safety/Documents/How%20the%20Polar%20Code%20protects%20the%20environment%20(English%20infographic).pdf accessed 20 September 2023.

[6] For example, if the maintenance philosophy is ‘repair by replacement’ then it assumes adequate spares being available and not having to cannibalize other submarines in maintenance for replacement parts.

[7] The percentage of time that a submarine must snort, when measured against the total time at sea, is termed the “indiscretion rate”. The lower the indiscretion rate, the less time the submarine must snort and therefore risk detection.