Early Days

The F-35 started in 1983 as the Advanced Short Takeoff and Vertical Landing (ASTOVL) program, and was initiated by the United States Department of Defense and the UK’s Ministry of Defense – under the leadership of U.S. research agency DARPA – to replace the Harrier jets in service with both armed forces.

The first few years saw four engine designs, but none of them proved capable of generating the lift required to get the aircraft off the ground. With that setback, it was decided that the ASTOVL program should temporarily be put on hold. But that didn’t last long. A short time later, an early variant of the Pratt & Whitney F119 engine (under development for the F-22) came to the attention of DARPA.

The discovery of that engine resulted in the continuation of the program, and in short order two unique engine designs – each based on the F119 – were proposed. Both the “Gas Coupled Lift-Fan” and the “Shaft Powered Lift-Fan” were theoretically powerful enough to provide the lift that the ASTOVL program required, but then a new problem emerged: the lack of any advanced airframes that could accommodate the new designs.

At this point, in late 1986, the UK Ministry of Defense backed out of ASTOVL and DARPA continued in secret with the designation “STOVL Strike Fighter (SSF).” After consulting with Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works about the prospects of developing an airframe, DARPA learned that they had a few designs that could be matured in order to accommodate either of the new engines. A complete blackout on the SSF program was then issued, and it continued along in relative secrecy.

Budget Bloating

In 1993, it was suggested that the Multi-Role Fighter (MRF) program, then on-hold as a victim of post-Cold War cuts, should be rolled into the SSF program. This decision was based largely on the idea that the performance of the SSF would include many of the abilities built into the design of the future MRF. This bloated the SSF significantly, and as budgets became tighter, F-22 production was cut short while the lifecycles of the F/A-18 C/D, F-15 and F-16 were extended.

The design and purpose of the originally envisioned ASTOVL program was unequivocally compromised at this point, turning the focused strike fighter/close air support joint platform into an aircraft expected to replace the F-15, substitute the shortfalls of the F-22, take over for the Super Hornets and replace the F-16s, A-10s and Harriers as originally planned.

A high price to pay

The F-35’s fly-away costs have long been the subject of much debate. Many insist the F-35 comes in at a cheaper price tag than the Super Hornet. I still argue to the contrary as all of the issues and setbacks (which remain ongoing) have driven – and will continue to drive – up the costs.

The one area that people seem to ignore is maintenance costs. Everyone is fixated on sticker price, but it’s important to look at the whole picture.

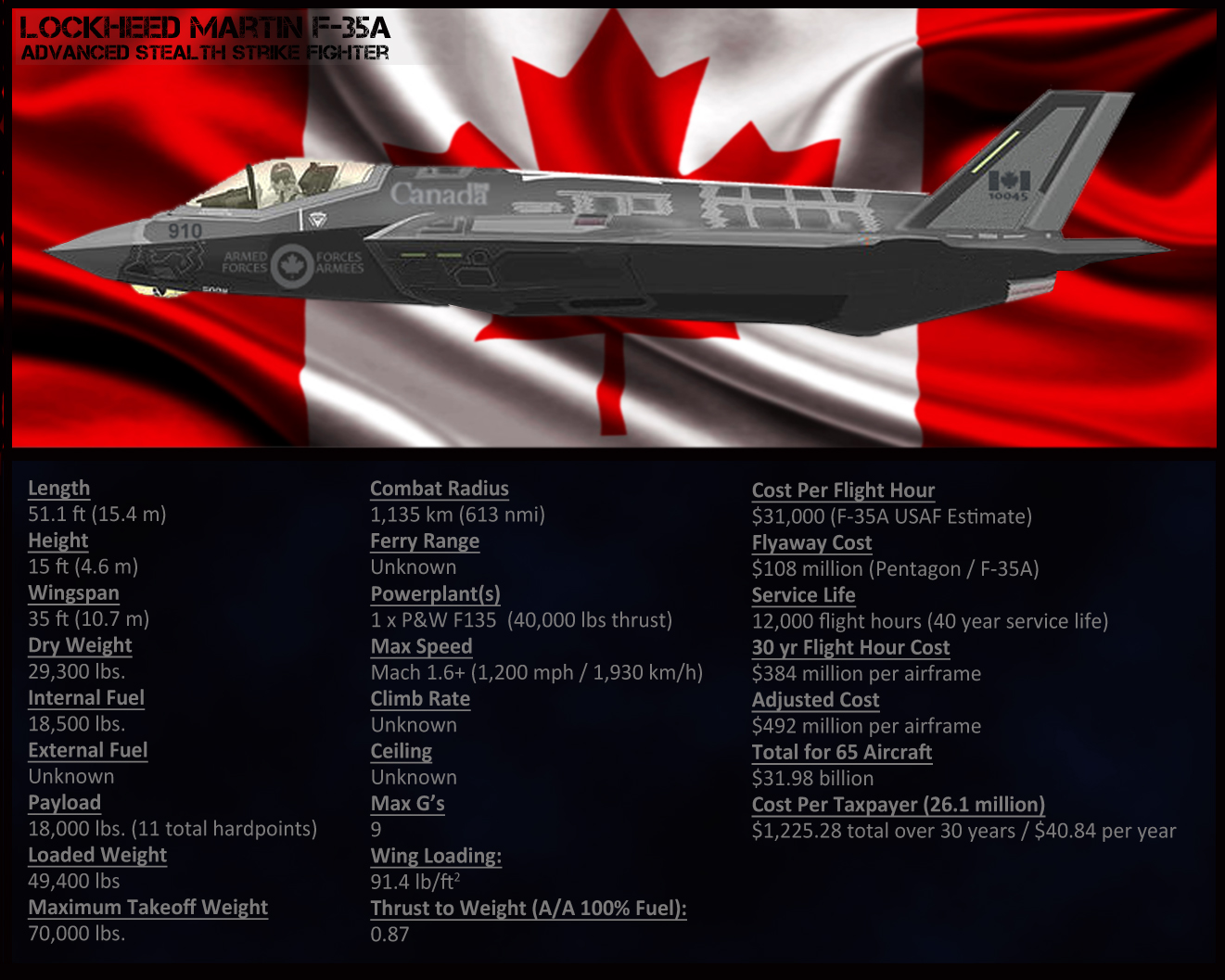

A short time ago, there were two documents, one published by the US Navy and the other, the US Air Force, which I heavily relied upon for cost estimates (I scoured the internet; they have recently disappeared). The US Navy document claimed a per flight hour cost of $35,000 (C) and the USAF claimed $31,000 (A). That’s not hard to believe when you realize the amount of high-tech sensors that have been added to the F-35 along with its various coatings and the higher airframe maintenance requirements. It’s far-and-away the most expensive aircraft to maintain, and that alone drives its price up far beyond its flyaway cost.

Another thing that the Gripen, Rafale and Typhoon all offer is final assembly here in Canada, a few years of support costs, and in the case of the Typhoon and Rafale, full tech sharing and design and modification independence. This means any cancellations in the home country of either aircraft have no effect on us; we can continue to build them and keep parts.

The F-35 offers no final assembly in Canada and no tech sharing (US laws make it all-but impossible), and while we are a third-tier partner in the program, unless Lockheed Martin cancels all its F-35 contracts with Canadian manufacturers, we’ll still be part of the program regardless of what fighter this country decides on.

In my opinion, the economic incentives the other fighters offer – and in the Hornet’s case, the ease of transition and maintenance – would offset any losses associated with Canada cancelling the F-35 program.

Praise for performance

When the six external hardpoints are used in addition to the four internal ones, the F-35’s stealth capabilities go right out the window. Realistically, however, the aircraft’s main SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) and strike roles do not require a ton of ordinance, relying less on firepower and more on precision strike capability. This is where the F-35 will shine brightly.

The F-35’s sensors and ability to track a large number of targets while simultaneously relaying that info to support aircraft after taking out defense and radar systems is extremely valuable in the opening stages of a war. Think of it as a stealthy fighter variant of an AWACS which can identify and track air and ground threats in real-time at any point in a mission while carrying out precision attacks on high value targets, largely undetected.

Sounds amazing doesn’t it? Well, none of it means anything to us… the US and UK will have large fleets of F-35s in the event of war and our discretionary roles in any NATO (or other) conflicts dictate that we do not need anything that pricey nor that advanced with regards to strike capability.

Stay away from hungry enemies

Also of note is the F-35’s low thrust-to-weight ratio in air-to-air configuration with 100% fuel (sub 1.0): it’s inferior to both the F-16 and the Gripen, Typhoon and the Rafale (also sub 1.0). This makes energy management tougher and gives the F-35 an air-to-air capability similar to the Super Hornet, making it a quick meal for the SU-27, SU-35 and PAK-FA. Ergo, it isn’t an air superiority aircraft in any way and also lacks the speed to effectively “bug out” if required. But don’t hold that against it too much… Lockheed Martin insists the aircraft was never designed for air-to-air combat in the first place.

Too good for Canada?

The F-35 is an amazing strike fighter and it will truly be a force to be reckoned with on the battlefield within the scope of its primary roles. It’s also the completely wrong choice for Canada as we really have no use for an advanced strike fighter in this country. We simply aren’t in the same threat zone that the US, UK and Australia find themselves in, and we lack the support structure the F-35 would need to unleash the capabilities it boasts. The only way the F-35 makes sense is if we decide to go with a mixed fleet, and even then, we just simply don’t need that much.

We also have a Navy to think about, along with search and rescue. Canada is, in terms of population, a small country; we need to think like one and ensure we have the most effective tools for the job within the scope of the threats we will realistically face. Roughly 30 million taxpayers is a much smaller base to draw from than the over 300 million that the United States has.

Help us out, America

Russia is an ever-present threat in the Arctic, but the US is part of NORAD and would be part of a combined response if Canada faced any aggressive moves within that region. As such, we need an interceptor which can integrate effectively with the F-22s and F-16s currently filling a rapid response role in Alaska.

We also need an aircraft capable of daily Arctic patrols. The way I see it, all of this makes the F-35 almost completely irrelevant for Canada. It can do some of these roles no doubt, but why would we pay double for an aircraft that will never make use of its primary features? It’s like buying a Ferrari and never being able to take it to the racetrack.

Food for thought if nothing else.

Chris Black has been an avid aviation enthusiast his entire life and is a former Air Cadet with 618 Queen City based at HMCS York. His love for all things aviation coupled with missing out on becoming a fighter pilot led him to begin writing as a way to share thoughts and ideas with fellow enthusiasts. His blog, On Final, and it’s accompanying Facebook and Twitter accounts can be found here: onfinalblog.com / facebook.com/onfinalblog / twitter.com/onfinalblog

Comments are closed.