Better Decisions. Safer Soldiers. Faster Fielding.

Since the award of the Tactical Communications, Command and Control System/Iris System contract to General Dynamics Mission Systems–Canada almost 30 years ago, Canada has invested almost $3 billion to evolve this capability to the current Land Communications, Command, Control and Computers Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (LC4ISR) system of systems, which is integrated into every Canadian Army platform.

The projects outlined by the Canadian Armed Forces in Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE) include the next evolution of the LC4ISR System. Once integrated, into an evolved Land C4ISR and fielded, the capabilities delivered by these programs will allow the Canadian Army to succeed in the future operating environment.

While offering a huge potential advancement for the Canadian Army there is also potential risk. If a holistic approach to definition and procurement is not taken, the capital expenditures could result in an ever-expanding set of stove-piped solutions that make the system harder to manage, deploy, operate, and train. Additionally, the resulting solutions may not achieve the desired operational effect.

More Than a Network

The System of Systems that underpins all of these modernization projects is the Canadian Force’s Land C4ISR System. The Land C4ISR System is a complex system of systems composed of hundreds of components with thousands of possible physical configurations. Best known for its networking capabilities, when coupled with the soldiers that use it, the Land C4ISR becomes a highly dispersed decision support system.

The goal of this system is to provide soldiers at every echelon with information superiority. By moving data across the network, turning it into information and presenting it to users in a meaningful manner, the Land C4ISR provides a higher level of knowledge, enhanced situational awareness, and helps soldiers in the field make better decisions.

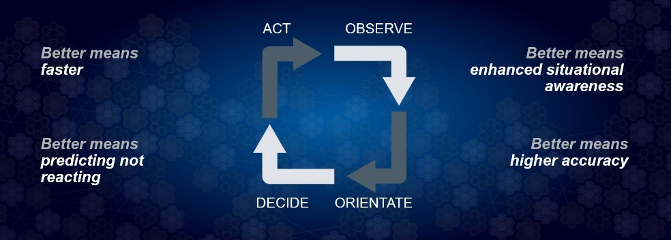

“The goal is not to adopt technology for technology’s sake,” explains J Sotropa, Chief Engineer, Land and Joint, General Dynamics Mission Systems–Canada. “Any technology insertion must add operational value. We need to help warfighters do their job better. In the case of tactical communications and information systems, we focus on the speed and accuracy of decision making; essentially tightening the OODA loop.”

The Brigade as a Platform

While the concept of a highly dispersed decision support system provides a useful frame of reference to assess the efficacy of individual technologies, to deliver a cohesive, integrated System of Systems, a physical system definition is required. To address this, General Dynamics believes we should consider the Brigade as a Platform (BaaP).

“At some point you have to move past the abstract to tackle the concrete issues of baseline management, system deployment, and institutionalization. We need a physical boundary,” added Sotropa. “Just as all systems on a ship need to work together and all systems on a plane need to work together, the land domain needs a bounded, comprehensive physical form to which we can apply good systems engineering.”

Defining the Brigade as the physical scope at which the system is maintained and evolved enables the alignment of people, processes, and tools to achieve mission and program objectives. This increases project efficiency and decreases overall cost by providing a framework for the Land C4ISR portfolio of projects. This focus expedites the process of prioritizing high readiness units with a specific mix of mission essential elements while maintaining flexibility to train, project and sustain forces across the spectrum of operations.

A Better Way

As Canada matures and evolves the LC4ISR System there are important considerations for how the system will work as a cohesive unit while supporting pan domain force employment. Even with the best intentions, many of the components that support key requirements could end up being duplicated across multiple programs resulting in a host of solutions with disparate services, hardware, and capabilities.

“Without a holistic, portfolio level approach, each program could deliver a bespoke closed system that employs its own protocols, connections, translations, and interfaces. Individual programs could deliver 100% of the requirements but overall the System of Systems could still fall short in maximizing operational benefit,” added Sotropa.

As capital programs move from definition to fielding, each will procure many different system elements, whether that be sensors, effectors, communications equipment or software applications. By introducing these different solutions, the Army may inadvertently be creating an operating environment that is incredibly difficult to use, expensive to maintain, almost impossible to train, and more vulnerable to cyber threats.

In an effort to avoid this, the procurement of these disparate information systems should seek to leverage the investment already made in the Land C4ISR.

Not only will this approach reduce integration risk, it additionally focuses on procuring new capabilities instead of on duplicating existing capabilities. Furthermore, a System of Systems aligned to a common enterprise architecture will allow the Army to quickly reconfigure the system to support evolving Adaptive Dispersed Operations.

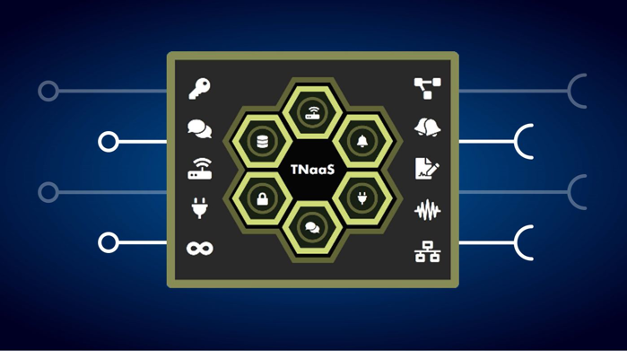

The Tactical Network as a Service

To address this challenge, General Dynamics has developed an approach called the Tactical Network as a Service (TNaaS). This approach allows Canada to consider the existing Land C4ISR, and its ongoing evolution, as a service provided to future programs. At its core, the Land C4ISR houses a common set of services built within an architectural framework. As driven by future operational and programmatic needs, these core services and infrastructure can be re-used where available and evolved as required.

The TNaaS allows Canada to maximize the reuse of its prior investment and reduce the overall cost and risk of delivering capital programs. The commonality in the fielded system will also reduce the training burden, expedite the institutionalization of the system and lower the total cost of ownership. Leveraging a common architecture also enables the creation of a unified C4ISR roadmap for the adoption of new technology.

“We believe this idea to be applicable to the full portfolio of SSE and SSE 42 projects specifically. By reusing a common core set of services, the Canadian Army can maximize the funds allocated to sourcing new capabilities, reduce the training burden, and shorten the institutionalization period,” said John Fisher, Director of Canadian Programs, General Dynamics Mission Systems–Canada.

Good for Canada. Good for Soldiers. Good for Business.

Utilizing the ideas described above will provide economic benefits to Canada, support the Industrial and Technological Benefits and Value Proposition policy, build the country’s industrial base, maximize value for taxpayer dollars, and provide a value-driven solution over the lifecycle of the LC4ISR System.

For soldiers, the operational benefits lie in the ability to make better decisions and an increased flexibility to operate independently or as part of a larger joint or coalition force. Maintaining continuity of the core services and the primary user interfaces while peripheral devices and services are added increases usability and trainability.

An established open architecture allows for rapid technology insertion and allows industry partners to develop with confidence and invest with a view to an established system roadmap.

“Working together in a shared technology and process framework, Canada and industry partners can provide real value to soldiers. We are excited by the possibilities offered by the future portfolio of programs and the impact it can have on the Canadian Armed Forces,” added Fisher.