Canada’s Arctic is changing, as is Canada’s Arctic policy. What does that mean to national defence needs and operations in the North? To discuss that topic, we spoke to Lee Carson, President of NORSTRAT Consulting and Senior Associate at Hill+Knowlton Strategies in Ottawa.

For those of us not that familiar, please tell us what we need to know about Canada’s North and how it’s changing.

I’d be happy to. At the most basic level, let me describe Canada’s North in terms of a redefined acronym: “RSVP”. The North is Remote, Severe, Vast, and Populated.

Remote: Sure, Canada’s North is far away from those of us living along Canada’s southern border, but it’s far more remote than just the

Severe: We all know it can be cold up there in the winter, and that the cold can have an adverse impact both on systems meant to operate in the North, and the people required to keep them operating. But think of a broader definition of severe: consider the impact of having to deal with 24 hours of darkness in the winter, or cope with heavy ice or permafrost, or the lack of basic infrastructure for communications, power or shelter that we take for granted in the South.

Vast: Canada’s North is large– as large in fact as all of western Europe, and just as diverse. We should no more expect that the characteristics or the needs of one region of Canada’s Arctic

Last, but certainly not least, Canada’s North is Populated. While that statement sounds obvious, it is all too often overlooked by southern business people looking North. Many of those people are Indigenous, with whom Canada has negotiated and signed a Land Claims Agreement giving the people exclusive rights over the land and what happens on it. And the cultural differences between Canadian Northerners and Southerners

It is only since the 1960s that Federal laws brought people in off the land and into new communities built around schools. As a result, we have a very young society less than three generations old, still at a very early stage of building many of the capacities we take for granted in the South.

While much of what I’ve just said is fairly constant, there is a lot about the North that is changing and changing quickly. Climate change is having a profound effect, with rates of change over twice that which we are experiencing in the South. That opens up new marine transportation possibilities, while closing down some land routes like ice roads and railways. Globalization is also having an impact, and a larger potential impact, with other countries looking to Canada’s Arctic for new shorter trade routes and for new sources and export markets for natural resources. And the geopolitical threat picture is unstable at best, with Russia investing heavily in new weaponry and Arctic infrastructure, and NATO straining under current political tensions.

Prime Minister Harper seemed to be a big proponent for Arctic defence procurement. What’s the current status?

Yes, Prime Minister Harper was a strong champion for Arctic Defence. Aside from publishing his Northern Strategy, he is remembered for his annual August Arctic tours, carefully planned around military exercises, scenic backdrops, and spending announcements.

In August of 2008, he said, “To develop the North, we must know the North; to protect the North, we must control the North.” That really provided a framework for all of his Northern defence initiatives, including the RADARSAT Constellation Mission, the Northern Watch Technology Demonstration Project, Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship, the Nanisivik deep water port, the Arctic Training Facility (Land) at Resolute, a polar class icebreaker, and others. While there have been successes, history has not always been kind to these projects– largely, I would argue, due to failures to deal with one or more of the RSVP aspects, either in procurement or in execution.

Where are we now under the current Government?

The Liberal government, under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has taken a different tack, beginning in December 2016, when he announced he was tearing up the Northern Strategy and replacing it with a new Canadian Arctic Policy framework, to be codeveloped in collaboration with Indigenous, territorial and provincial partners.

Simply put, whereas Harper’s Arctic was all about the land, Trudeau’s Arctic is all about the people. This means a much greater focus on individual and community capacity building, including health care, housing, education, energy, and other social infrastructure needs.

While at first glance, that switch in focus suggests a reallocation of funds from military hardware to social infrastructure, it is simply not the case. The defence needs of the Arctic have not gone away; indeed, they have become more pressing for the “changing Arctic” reasons I touched on above. However, what has changed is the need to truly take into account the “P” of RSVP when planning for, bidding or executing those systems. Just as we have become used to dealing with the Industrial Technology Benefit aspects of defence procurements in the South, we must be mindful and become masters of building true Indigenous partnership and meaningful capacity building elements into our defence procurements of the North.

How is that working? Can you give us some examples?

Yes, I think it is working even though we are just starting out. It makes for a very exciting time to be working in the Arctic. I’ll talk about a few examples that I’m working on.

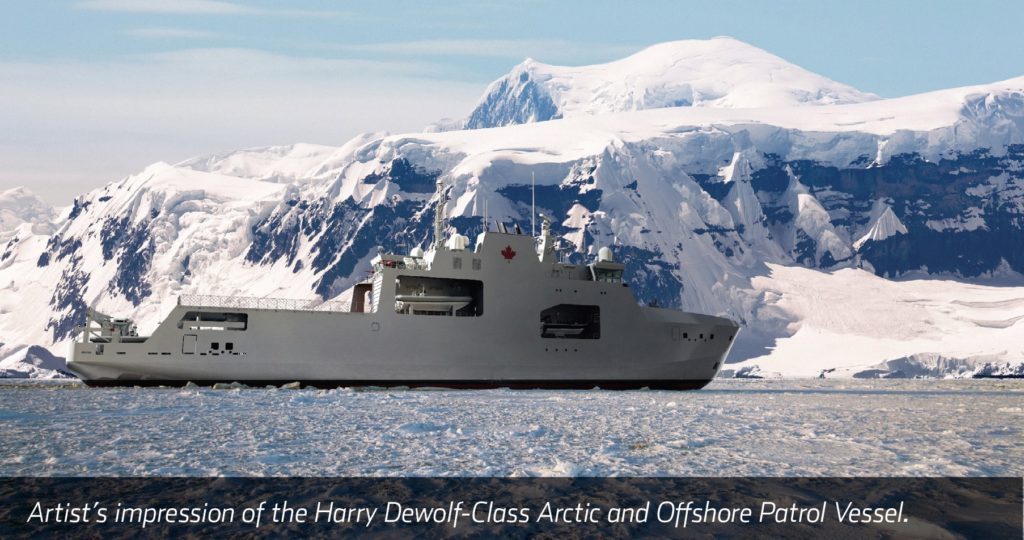

AOPS: AOPS construction continues in Halifax where the first ship will be launched later this year. And while there’s little doubt it will be an impressive and capable ship, it still doesn’t have a clear and pressing Arctic mission, at least in terms of capacity building aspects I’ve just described. With that in mind, the Navy is currently on an outreach mission, led by Commander Dan Manu-Popa and supported by Honorary Captain (Naval) Tom Paddon to engage with the Inuit and identify opportunities.

Meanwhile, the Canadian Government is, in parallel, aggressively pursuing an Innovation Agenda, including establishing Innovation Superclusters like the Ocean Supercluster centered in Atlantic Canada.

And while arctic needs and related innovative solutions are expected to be a strong focus of that Supercluster, the remoteness and vastness of the Arctic will make the cost of deploying and testing arctic innovations prohibitive.

Suppose one or more AOPS were to be deployed as a floating platform for those arctic innovations to be tested? And further, what if the crew of the AOPS was not just made up of the traditional navy sailors, but also Inuit elders and other experts who could impart their traditional knowledge of the North as well as their unique expertise to the innovators, making their innovations more successful, more useful, and more efficiently developed? And what if those innovations, in turn, led to further positive development and progress of Arctic marine transportation corridors, Inuit coastal communities, and Canadian defence and sovereignty?

North Warning System In-Service Support: The NWS sustainment contract is coming due for renewal. And since the current contract was let, the Government of Canada has negotiated some major agreements with the Canadian Aboriginal governments including the “Inuit Nunangat Declaration on Inuit-Crown Partnership Agreement” and the Nunavut Settlement Agreement, including Article 24 relating the procurement by the Government of Canada of goods, services, leases, and construction delivered within or into the Nunavut Settlement Area.

Those agreements, coupled with the growth in business acumen and capacity of the Inuit Development Corporations, sets the stage for Inuit-owned corporations to take a prime role in the management and execution of a long-term contract with the Department of National Defence for North Warning System in-service support.

And, analogous to the approach the Department of National Defence is now taking with awarding long term in-service support contracts for naval ships, the length of which allow and incentivize the prime contractor to make significant investments in productivity improvements, an Inuit-led NWS ISS contract would enable the Inuit prime contractor to make and execute a comprehensive and truly significant capacity building plan.

Future Fighter Capability Project: On July 21, 2016, Prime Minister Trudeau announced that: “We will immediately launch an open and transparent competition to replace the CF-18 fighter aircraft. The primary mission of our fighter aircraft should remain the defence of North America, not stealth first-strike capability.” The prominence of the North America defence mission coupled with the increased Arctic threat environment, primarily Russian, strongly suggests increased importance of Arctic missions and use of

Which, in turn, if properly planned and executed, includes win-win outcomes between the RCAF and the FOL communities for growing the capacity and economic wellbeing of those communities while contributing to the effective and efficient support of Canada’s future fighter fleet.

Icebreaker Capacity: The Canadian Coast Guard’s icebreaker fleet plays an essential role in enabling the delivery of vital fuel, food and cargo to our isolated Northern communities. However, with an average age of 35 years, the entire fleet is approaching end of service life, requiring more and more repair work, during which the vessels are not reliably available for service.

This situation has many adverse impacts, up to and including the very survival of the Northern communities which rely on the sealift for their supply of goods. But it also has economic impacts on the Northern economy and safety impacts on the crews of the icebreakers and the vessels they are escorting.

“In August of 2018, the Government of Canada announced the purchase of three medium commercial icebreakers which will help to ensure continuity of service for Coast Guard clients and the safe passage of marine traffic through Canada’s waterways.”

These ships will provide an interim capability for the Canadian Coast Guard, while replacement vessels are being built under the National Shipbuilding Strategy.

Thanks for sharing your insight on the North with us. In closing, given the shift from land to people, how will this benefit Canada as a whole?

It really comes back to the concept of partnership. First of all, Inuit are part of our Canadian “whole”, just as are southerners. Beyond that, they have their own unique and complementary perspectives, knowledge and skills gained from living and working in Canada’s North. I think Canadians have intuitively understood for some time that the potential of Canada’s North to all Canadians is great, whether it be to our enhanced resource wealth, or our national security, or to our environmental and cultural heritage. “The true North strong and free”. It’s time for us to understand that potential can only be effectively shaped and achieved in partnership with the people who know it and own it.

This article first appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Vanguard.