Residents of the Canadian Arctic are painfully aware of climate change and more specifically global warming. Their lives have been and continue to be affected directly. Some have died because the traditional safe routes over the ice are no longer predictable.

Depending on a given location in the Arctic Archipelago, one of the more noticeable impacts of global warming has been the disappearance of arctic sea ice for extended periods. For several intervals in 2020, the ice in the Arctic was at its lowest point on record. The open waters have made entrance to the Arctic Archipelago more accessible. However, the growing loss of sea ice for longer periods has also meant increasing multiyear ice moving about unpredictably by currents and winds. Although commercial traffic has not increased significantly, the new access has attracted many adventurers and cruise ships in search of new exotic and exciting destinations. Many of them are ill-prepared to venture that far north in an area with extremely limited infrastructure and challenging communications.

It has been widely reported that the Arctic is warming at twice to three times the rate of southern locations. There is increasing evidence that arctic storms are getting stronger. They increase the risk for adventurers and ships that run into problems because of a fire, loss of power, or loss of steering capability.

A 2019 incident involved a large cruise ship that lost power in a storm and was being pushed to shore in Norway. The Viking Sky, with some 1,300 people on board, started to evacuate passengers by helicopter. Heavy seas and strong winds made the evacuation extremely difficult because the cruise ship lifeboats could not be used safely. Several helicopters managed to extract some 400 passengers by the time the crew managed to restart one engine and avoid running aground. A similar situation in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago could easily turn into a disaster given the paucity of infrastructure and the distance from major SAR assets.

Marine Search and Rescue in Canada is the responsibility of the Canadian Coast Guard. Until recently, most marine search and rescue responses would have been conducted by the Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers that deploy every summer in the Arctic, mainly in support of the community annual sealift re-supply operations, or by vessels of opportunity. The Coast Guard ships, which are often equipped with a helicopter and a rigid inflatable boat, can provide a rapid response to incidents especially if within the range of their helicopters. They can also sail at best speed to reach the site of an incident. Since 2017, they have been deployed to the Arctic sooner and departed later, which increases their availability for SAR.

On the land, the territorial governments of Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut are responsible for locating missing people. In the Arctic, that task is normally delegated by the governments to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who are contracted to provide community policing. One of the most effective community-based resources they can call on is the Canadian Rangers of 1 Canadian Ranger Patrol Group. These voluntary members of the Canadian Forces Reserves have earned an outstanding reputation in support of their communities. Their intimate knowledge of the land and weather conditions is unmatched. When a person is reported as missing the Canadian Rangers are often one of the first agencies to be contacted for help. They generally do this on a voluntary basis as members of their communities, but they can be formally tasked to do a search in which case they are compensated.

The search and rescue for missing and over-due aircraft or aircraft accidents that trigger an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) is the responsibility of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The RCAF maintains a Major Air Disaster response capability that can be parachuted to support a major SAR operation anywhere in Canada. Based on the assessment of the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC), SAR assets will be dispatched to investigate the situation or locate the missing aircraft. This is typically done with CC-130 Hercules aircraft tasked as primary SAR assets. The Twin Otters of 440 Squadron based out of Yellowknife and CP-140 Aurora based in southern Canada have a secondary SAR role and could potentially be tasked as well. The JRCCs can also call on community-based assets of the Civil Air Search and Rescue Association (CASARA) to support a given search effort. Unfortunately, the Hercules and Twin Otter aircraft rely heavily on visual search methods and lack many of the more sophisticated electronic search sensors to support the searches. This is about to change.

SAR Improvements

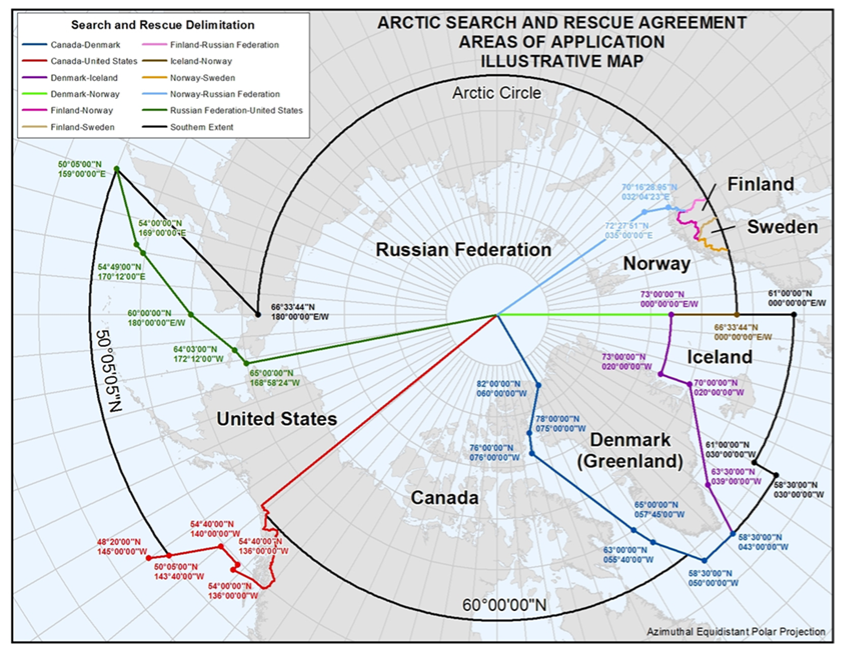

So where are the improvements? Let’s start with international co-operation. On 12 May 2011 in Nuuk, Greenland, the Arctic Council members consisting of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States established an international treaty called the Cooperation On Aeronautical And Maritime Search And Rescue In The Arctic. The members of the Arctic Council are all too familiar with the scarcity of search and rescue assets in the Arctic and the challenges posed by the huge distances and the weather. They agreed to increase the coordination and sharing of SAR assets. As depicted below, Canada will be responsible for a very large area that goes all the way to the North Pole.

With arctic countries agreeing formally to help one another there is an increased likelihood of better outcomes. Canada will surely benefit from American and Russian ships that are frequently present in the western part of the Arctic and from Danish ships on the eastern part of the Arctic Archipelago. A recent example of this benefit was the assistance provided in 2016 by the Danish Coast Guard to the F/V Saputi, a Qikiqtaaluk Fisheries Corporation fishing vessel damaged by ice in the Davis Strait[1].

The United Nations International Maritime Organisation has recently published a new Polar Code. The Code took effect on 1 January 2017. It recommends and imposes a multitude of standards to be met by shipping companies that wish to operate in the Arctic and Antarctic. The combination of those standards is expected to reduce the potential of incidents in the first place through its obligatory training and equipment requirements. The mandatory equipment on board should also allow the immediate survivors of an accident to safely evacuate a ship in distress if need be while waiting for the arrival of SAR assets.

Thanks to Canada’s Ocean Protection Plan funding, the Canadian Coast Guard established an Inshore Rescue Boat station in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut in June 2018, and has been providing several Arctic Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary (CCGA) units with training and a well-equipped community boat with search and rescue equipment. There are 20 CCGA community-based units in the territories and the northern part of Quebec and Manitoba. Twelve of them have received a SAR community boat. The Inuit know their marine environment including weather patterns, currents, tides, wildlife as well as where hunters and gatherers would generally go to. Should a fisherman or hunter be reported as missing, the CCGA unit would be able to conduct a more efficient initial search while other SAR assets are being deployed. They provide a very valuable addition to the local marine SAR capability.

In terms of technology, one of the more recent developments has been the ability to receive and track Automatic Identification System signals (AIS) from space. This technology allows a marine unit in distress to transmit a signal that will include the position of the vessel using an Automatic Identification System SAR transmitter. Knowing the exact position of a vessel in distress greatly simplifies the deployment of assets to the scene. In SAR incidents, accurate information is extremely important. Knowing exactly where a vessel is, as well as the number and severity of personal injuries, etc. allows for a more effective execution of the search and the rescue. The AIS signals will also help identify other vessels nearby that could provide assistance. It will allow for a better coordination of the SAR efforts.

Beginning in 2021 the Royal Canadian Navy will start deploying its new Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships of the Harry Dewolf class to the Canadian Arctic. Those ships are equipped with a helicopter as well as a rigid inflatable boat. They will be a major addition to the Coast Guard’s existing search and rescue capability.

In the realm of enhanced Canadian SAR capability, Canada has recently purchased a new fleet of search and rescue aircraft to replace the aging CC-115 Buffalo aircraft which were first delivered in 1964. The new Airbus C295W, called Kingfisher, is equipped with the latest fully integrated search technology. It includes the L3 Wescam with an electro-optic and infrared cameras, the Elta search radar, two satellite communications suites, and night vision goggle compatible with a heads-up display with an integrated Enhanced Vision System. The combination of these systems will make the aircraft extremely efficient at locating personnel and vehicles in almost any weather conditions, especially against the colder background of the Arctic. The aircraft is capable of low speed in the search mode and good transit speed to the search area. Its agility, long-range and modern search equipment will substantially enhance Canada’s northern SAR capabilities.

Lastly, Transport Canada is in the process of acquiring a long-range drone for its National Aerial Surveillance Program. The drone will be equipped with advanced sensors that will provide the JRCC an additional option to support a search if the drone happens to be in reach of the search area.The sum of increased assets and the new sophisticated systems being deployed now and in the coming years will significantly increase the effectiveness of search and rescue operations in the Arctic.

[1] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/saputi-crew-return-iqaluit-friday-1.3464995