In one of my first Tech Watch columns in Vanguard published in 2014, which came out after the announced changes to the previous Industrial Regional Benefits policy in Canada. The changes, which would incentivized defence contractors to focus investments in Canadian technologies that would contribute to Canada’s long-term technology objectives, caused me to be exuberant and idealistic about the role that the global (mostly U.S./North American) defence industry could have in driving the Next Generation technologies that we (as in, consumers) would eventually use in our everyday lives.

At that time, I was always throwing around examples such as: “If it wasn’t for defence research, we wouldn’t have GPS, the microwave, or even the internet!” I still believe that Skunk Works, the National Research Council and industry all play critical roles – among others in the community – in the research and development of unique defence-related technologies. However, I now believe the act of innovating is getting a whole lot more complicated. We have been hearing for years about the exponential changes that will be driven by digitization, and how we will travel along the “Moore’s Law” curve and undoubtedly have trouble keeping up as humans.

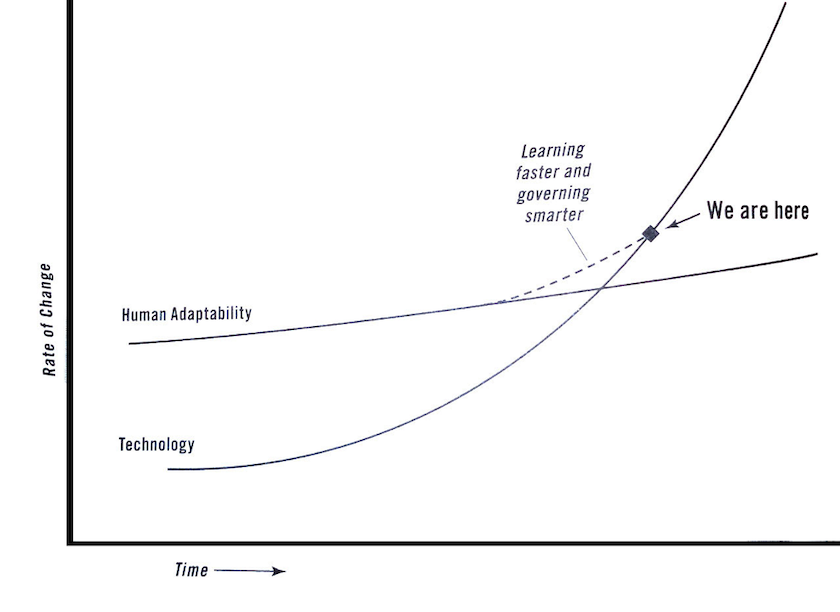

I have lived by this image for the past five years, assuming that we would all travel nicely in a polite Canadian lineup, upwards along the bend. Still today, only 18 per cent of North American Business to Business interactions are digitized, and our ability to adopt technologies, especially to use day to day, is lagging way behind technology’s development itself. While I’ve always thought we would have a neat and tidy exponential increase in technology development and that we would always struggle to keep up, I just don’t think it is that simple anymore. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are allowing processes, people and entire sectors to experience stepped increases instead of the neat, exponential travel up the curve. Everything is going peer to peer, eliminating middlemen, and turning old power structures upside down, dramatically changing the way we interact, work and will likely fight wars and defend ourselves.

To explain a rather extreme example of technology disrupting a traditional power structure, I would like to share an example from a new a book that I highly recommend, “New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World – and How to Make It Work for You” by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms. I received it as a gift from the new CEO of arguably the most entrenched, traditional organization in Canada, the Business Council of Canada, made up of the CEOs of the largest corporations in the country. Even they see this coming – big time.

The example the authors provide to demonstrate this shift is of how ISIS, the all-terrifying powerful enemy of the world, recruits people online. One of their “powerful” forces is a woman named Aqsa Mahmood. She attended a private school in Scotland, listened to Coldplay and read Harry Potter books. She was converted somewhere along the way and started to convert others online to join her. She used seductive tactics to lure people in, relating to them, leveraging her networks, and offering practical peer-to-peer personal advice, such as “bring coconut oil.” Coconut oil, I have learned, is great for hair, skin, and cooking – who knew? She was known to work sideways luring in girls and then leveraging them to lure in others, as opposed to top down. Meanwhile, to combat these recruitments, the U.S. Department of Defense continued to drop leaflets from aircraft overhead with scary images of what happens to women if they join forces with ISIS. After years of doing this, they realized they needed a “digital strategy,” so they set up a Department of State Twitter account to respond to some of the online messages being sent back and forth on the topic of recruitment. At one point, a giant message from the Department of State Twitter handle came out in bold saying, “THINK AGAIN! TURN AWAY!” to those considering joining ISIS. This is one odd example where traditional military hierarchies come up against these new, networked approaches, leveraging consumer-facing/Silicon Valley-developed technology, and there’s a clash. That is one battle lost against what we must assume will be more to come.

The new world that is emerging, driven by this steep increase in technology, is one where the global defence sector will want to consider what is being developed in the consumer sectors. There is going to be a messy, dramatic expansion in technologies, and I don’t believe it will be as straightforward as it has been in the past. This notion is a complete flip from one of my first Tech Watch columns, where I assumed defence innovation would lead most of the next generation of commercial sector technologies. I now think it will be a messy combination, at an extraordinarily rapid pace, requiring an entirely new way of looking at the world. It is no longer going to be enough to try to encourage our leaders just to embrace things like software and data; it will be about an entirely new way of looking at the world and how we lead through it.

Above all, I believe that this new style of leadership that will be required to thrive (and even survive) in this new world, will require a wider lens and be open to grabbing ideas from all over the place to adopt and adapt the way we lead organizations. Harvard Business Review concluded that organizations with “2D diversity” (i.e. diversity in background and experiences) in their leadership teams are “45 per cent likelier to report a growth in market share over the previous year and 70 per cent likelier to report that the firm captured a new market.” In other words, companies that are growing into new products and new markets today are open to seeing things differently and leveraging opinions and ideas from a diverse group of new leaders that are emerging. Above all, consumer-facing innovation and technologies being developed for a wide range of industries and use cases should all be considered when developing the future of defence technology. It won’t be good enough to think about technology development in the linear fashion I once thought, leaning on the same principles, companies, and types of leaders that we always did. Five years later, I’ve changed my view of technology quite a bit.

(Image: Pixabay)