After studying foreign aircraft including the F-16, F/A-18 and Dassault Mirage, Saab developed the imaginatively named “2105” (later renamed 2110).

The predecessor to today’s Gripen was engineered as a Mach Two-capable aircraft with an air-to-air emphasis and air-to-ground and reconnaissance capabilities, including the ability to takeoff from short, unprepared runways. The goal was also to reduce the size of the Gripen in contrast to the outgoing Viggen, while improving on payload, wing-loading capabilities and maneuverability.

The avionics and the fly-by-wire system intended for use in the aircraft were tested in the Viggen in 1983*. The Gripen, as it was later called during competition, required such a system because it was designed to be more aerodynamically unstable than the average fighter already in production at that time.

After a long period of final development, the Saab JAS-39 Gripen entered service in Sweden in 1997. The delays came primarily (but not exclusively) from two accidents that forced Saab to re-examine the Gripen’s systems and make several changes to improve safety and flight behaviour.

Fast forward to today, and the forthcoming Saab JAS-39 Gripen “NG” presents itself as a highly-capable, economical fighter aircraft.

One of the biggest selling points of the Gripen is its projected low maintenance costs, achieved by modifying the aircraft’s engine and airframe to deliberately reduce its total number of parts/components. According to Saab, fewer parts not only means less maintenance, but less downtime.

Another big selling point for the Gripen is its reasonable unit cost. Add final assembly in Canada to the equation and a few years of support costs and its value becomes a little clearer. Here’s an easy cost comparison:

- Total cost of Saab Gripen procurement x 1.5 = price of the Super Hornet procurement

- Saab Gripens x 2 = price of the Typhoon or Rafale

- Saab Gripens x 3 ¾ = price of the F-35

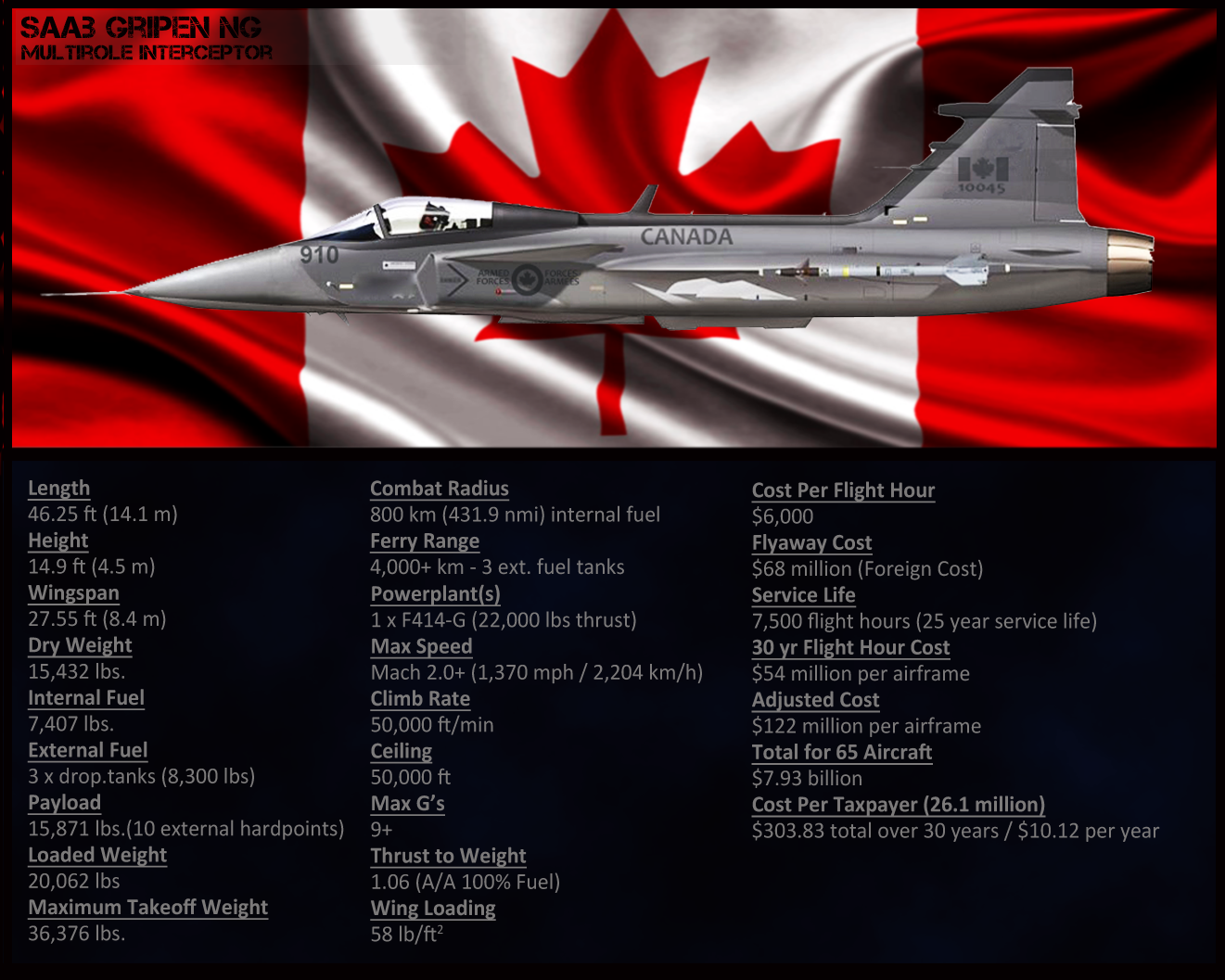

While the Gripen NG might be cheap in comparison, it can still boast impressive performance. The aircraft can sustain 9+Gs in a turn, and with a thrust-to-weight ratio of 1.06 in air-to-air configuration with 100% fuel, it is outclassed only by the Typhoon. It’s also capable of speeds in excess of Mach Two, and has a climb rate of 50,000 ft/min.

Where the Gripen NG falls a little short is in payload. It has the least payload capability compared to its rivals, and while it is capable of air-to-ground, it is less focused in this area than the F-35, Super Hornet and Rafale. This leaves it somewhat on par with the Typhoon, from what I have been able to find.

This isn’t necessarily a detriment, however. Part One of this series covered the requirements of the RCAF and CAF for the next fighter along with its planned duties. The Gripen NG meets every single one of our non-discretionary domestic obligations, including NORAD, and it is more than capable of meeting any discretionary role we play with NATO or in a global war scenario (keyword being discretionary).

The biggest drawback to the Gripen NG (that isn’t payload-related) is its single engine. In the Arctic, out over the Beaufort Sea (Russia’s historical breach point) a single engine, regardless of reliability, is a concern for obvious reasons. That said, unlike the F-35, which already has a troubled engine history, the Gripen NG makes use of — here it comes — a modified Super Hornet engine. This engine was based on the one fielded by the legacy Hornet, and has already proven its reliability in Canadian conditions.

That being said, two engines will always be better than one from a safety standpoint. I guess it boils down to whether the lives of our servicemen and women matter more than saving money. For me personally, the extra cost is worth it.

One other possible scenario would be the purchase of 100 Gripen NGs and 65 Typhoons for $29.49 billion (substitute the Rafale for $28.12 billion or the Super Hornet for $24.48 billion). If you compare that to a total cost of $31.98 billion for 65 F-35s; Canada would get two aircraft capable of meeting our domestic needs with the added flexibility of keeping a two-engine fleet for use over the Arctic.

If Canada decides to go “mixed fleet” it would need the Gripen NGs. There is nothing else in that price range that can boast its aforementioned capabilities. But, as a single fleet solution, I just don’t see it. And in the current CF-18 replacement fighter program, Saab doesn’t either. The company is currently not putting the Gripen forward as a contender — although with an election around the corner, things may change.

Given the likelihood of a mixed fleet somewhere between infinitesimal and zero, the Gripen NG loses out in my mind due to that single engine. Thus far, my favorite is still the Typhoon; however, on performance and cost alone, it’s hard to write-off the Gripen. I guess time will tell. Only an open and fair competition can truly determine what’s right. Everything else is just educated musings.

That concludes Part Four. Part Five will cover the F-35, the fighter that’s been front-and-center to Canadians for several years now.

* Fly-by-wire first appeared in the Avro Arrow, and interestingly enough, a very similar system made its way into the F-16. The Arrow was also the first delta wing and the German’s were the only other country at the time studying the feasibility as well.

Chris Black has been an avid aviation enthusiast his entire life and is a former Air Cadet with 618 Queen City based at HMCS York. His love for all things aviation coupled with missing out on becoming a fighter pilot led him to begin writing as a way to share thoughts and ideas with fellow enthusiasts. His blog, On Final, and it’s accompanying Facebook and Twitter accounts can be found here: onfinalblog.com / facebook.com/onfinalblog / twitter.com/onfinalblog

Comments are closed.