The security challenges confronting national defence organizations are both complex and dynamic. Nations around the globe now face a myriad of threats that vary greatly in both scope and scale.

Longstanding threats from neighboring nations, such as the enduring tensions on the Korean peninsula and Indian subcontinent, are the types of traditional challenges that most national defence organizations have been organized to confront.

But major terrorist attacks such as those of September 11, 2001 and, more recently, terrorist attacks in Paris, attacks on school children in Kenya and French satirical writers in Paris, typify the emergent challenges of ‘asymmetrical adversaries’ who possess destructive and disruptive capabilities that are more difficult to detect and defeat through conventional means – and thinking.

At the same time, in many Western nations budgetary challenges are putting downward pressure on defence spending. Faced with significant and growing government entitlement costs, sluggish economic growth, and weariness after over a decade of overseas operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, defence budgets for many North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Allies and partners have dropped substantially in recent years.

Despite aggressive moves to cut overhead costs, and efforts to operate with like-minded nations in coalitions, many of these countries continue to struggle to modernize outdated systems and maintain readiness as the security environment facing ministries is both uncertain and increasingly complex.

Other nations face different challenges that are no less complex. Some, like Ukraine, face existential security threats that are driving their defence priorities. Other states, such as Japan and Poland, are being confronted by an aggressive China or revanchist Russia, respectively.

In the Middle East, the Gulf States such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and Bahrain, are in the center of a regional neighborhood whose stability has been decreasing in recent years. Overt challenges from Iran, instability in neighboring nations (e.g. Yemen, Syria and Iraq), compounded by declining oil prices, are having a major impact on internal and regional stability.

These wide-ranging challenges leave defence leaders with tough choices. To examine these challenges, we have assessed the impact on 60 nations from geographic regions around the world:

- Americas: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, United States, and Venezuela.

- Europe: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.

- The Middle East and Africa: Algeria, Angola, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates.

- Asia-Pacific: Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

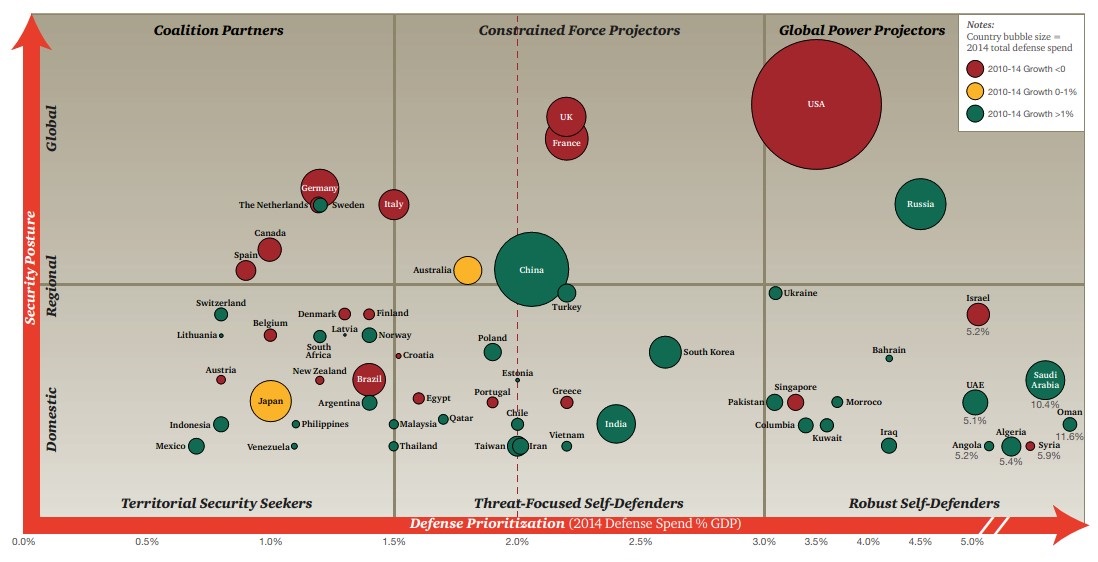

Our approach for developing these global defence perspectives looks at recent defence spending trends and the major investment, institutional, structural and strategic priorities and challenges impacting these nations. Using the insights and unique perspective of PwC’s Global Government Defence Network, we have measured and plotted these 60 nations against two dimensions: 1) how they prioritize Defence spending and 2) how they position or ‘posture’ themselves in the global security environment.

Mapping these nations on the basis of Defence prioritization vs. security posture results in a new Global Defence Map, as depicted in Figure 1.0.

Source: SIPRI, Teal Group International Defence Briefing, The Military Balance, IHS Defence Budgets, PwC analysis.

The six segments in this graphic outline distinct profiles reflecting the respective levels of defence prioritization and security posture.

Global Power Projectors: The United States and Russia. These two nations alone spend greater than 3% of their GDP on defence and are very engaged in security efforts around the world. These nations seek to use their military capabilities and security posture to influence global security issues.

Their defence organizations are very large and mature. Although not necessarily nimble, these organizations are capable of deploying forces, managing large complex procurements, and, at least in the case of the United States, conducting large- scale operations around the world.

Coalition Partners: Canada, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden. These six nations spend less than 1.5% of their GDP on defence, but they are very engaged in security efforts around the world. While these nations have modest defence budgets, they readily contribute to United Nations peacekeeping and multilateral coalition operations around the world. Except for Sweden, these nations are all NATO allies who have a strong track record of operating together.

Constrained Force Projectors: Australia, China, France and the United Kingdom. These four nations spend between 1.5% and 3% of their GDP on defence and are very engaged in security efforts around the world. These nations are among the world’s largest defence spending nations, who prioritize high-end Defence capabilities and have militaries that can deploy or exert their influence in most regions of the world.

Robust Self-Defenders: Angola, Algeria, Bahrain, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Syria, Ukraine and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). These fifteen nations spend greater than 3% of their GDP on defence but are more focused on security efforts in their immediate geographic region. Because of internal or immediate regional threats, these nations have developed military capabilities centered on directly and aggressively countering those challenges.

Threat-Focused Self-Defenders: Chile, Croatia, Egypt, Estonia, Greece, India, Iran, Malaysia, Portugal, Poland, Qatar, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam. These sixteen nations spend between 1.5% and 3% of their GDP on defence and are more focused on security efforts in their immediate geographic area. Many of these nations participate in UN peacekeeping or multilateral coalition operations to help build relationships with allies and partners, but the focus of their spending is on countering a specific threat emanating from a single nation.

Territorial Security Seekers: Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, Finland, Indonesia, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, South Africa, Switzerland and Venezuela. These seventeen nations spend less than 1.5% of their GDP on defence and are more focused on security efforts in their immediate geographic area. These nations spend modestly on defence, but many contribute to UN peacekeeping operations or multilateral coalition operations in some fashion.

Developments and Implications

The Defence Map’s diversity reflects the variety of the threats and challenges facing defence organizations around the world. Mapping defence prioritization and security posture create a more useful framework for analyzing these sixty nations. In addition to the segment, a number of broader insights emerge that should be of interest to Defence leaders around the world, and those who monitor them:

Expect Movement on the Map

There is a tremendous amount of growth in the lower half of the Map where 31 nations have seen the significant recent growth that is expected to continue in the next five years. But this raises important questions: how might countries like India, Japan, and Poland, for example, make efforts to increase their global security posture and move into the upper half of the Map over time? Conversely, persisting constraints on the Constrained Force Projectors may drive a shift down and left on the map for several nations in this category.

Global Players Under Severe Pressure The preponderance of nations that have a globally oriented security posture are also under significant budgetary pressure as evidenced by the fact that spending in ten of the twelve nations in the top half of the Map has declined or remained flat in the past five years. With generally flat Defence spend in these nations expected over the next five years, nations such as the United States, the UK, France, Australia and Canada will be hard pressed to maintain their robust level of global engagement in the coming years. To keep their current levels of security posture, these nations must prioritize readiness and training so that their forces can continue to conduct operational deployments as the security environment evolves. Moreover, these nations will face a difficult balance maintaining their technical edge in challenging fiscal environments.

Find other engaging content

in the Dec-Jan 2016 issue of Vanguard Digital. Click here.

Cost-Cutting Dominating Strategy Institutional reform efforts focused on cost-cutting are a major emphasis among almost all of the nations that have a globally-oriented security posture. Global Power Projectors (such as the United States), Constrained Force Projectors (like the UK) and Coalition Partners (such as Canada) are all undertaking initiatives to increase efficiencies and reduce overhead or personnel expenses. These efforts are being accompanied by a mandate for greater cost-consciousness and accountability for defence assets.

A Focus on Institutional and National Capacity

Furthermore, institutional reform efforts focused on capacity-building are a priority principally in those nations in the lower half of the Map. Robust Self-Defenders (such as the UAE), Threat-Focused Self-Defenders (like India) and Territorial Self-Defenders (such as Japan) are less focused on efficiencies than on building the institutional capabilities of their respective ministries of defence.

Collaboration in Procurement. Cooperative efforts are particularly prevalent among the nations that have lower levels of defence prioritization. Cooperative procurement efforts, for example, are much more prevalent among the Coalition Partners and the Territorial Self-Defenders than the Robust Self-Defenders. That being said, the elevated costs of major weapons systems, such as the F-35, is driving broader international collaboration even among major defence spenders who have large budgets.

Asymmetric Threats and Cyber “Insecurity” Gaining Prominence. Regardless of where a nation currently resides on the Map, vulnerabilities to asymmetric threats such as terrorism and cyber-crime/attack are driving investment in new, non-traditional defensive and offensive capabilities. Such investment has profound implications for the nature of the future forces with respect to recruitment, training, career development and retention.

Jeffrey D. Rodney is Director/VP, Consulting & Deals – Government Defence at PwC. Jeffrey has over 15 years of management consulting experience in the area of operations effectiveness for Fortune 500 companies and the public sector.