As the CF-18 replacement program languishes on, people are starting to lose sight of the established requirements for our next fighter; instead, attention has been diverted to spec sheets, where the search for the “best” aircraft (at least on paper) has been a hot topic amongst armchair pilots.

If it were only that easy. There are many more items to consider than simply “which aircraft looks better on paper and pushes certain envelopes better.” Every aircraft has strengths and weaknesses; it’s a matter of finding the most favorable balance between those traits and the budgetary and political restraints of the procurement process.

The first item to touch on is the idea of a mixed fleet. According to the Department of National Defence’s Mixed Fleet Report, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) would need two aircraft types, lodged under the headings “Group A” and “Group B”:

- Group A aircraft would have to have be at least 50% cheaper to acquire than Group B aircraft for a break-even or less cost scenario versus a single fleet of highly capable aircraft.

- Thirty-eight Group B aircraft would be needed to meet Canada’s non-discretionary domestic patrol and NORAD requirements and 34 Group A aircraft would be needed to meet Canada’s discretionary NATO roles.

- Sixty-five aircraft are shown to be more than adequate to cover any and all requirements for Canada’s Air Force within the scope of the report.

Based on this, and other published information on the topic, there are possibilities for a mixed fleet, but the problem comes down (as usual) to cost. In my opinion, there aren’t any aircraft that allow for a mixed fleet to improve our capabilities overall within budget.

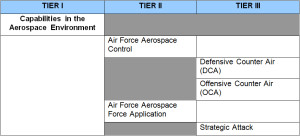

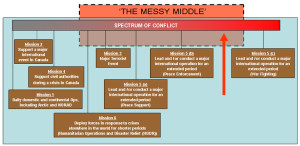

The majority of the CF-18 replacement’s duties will be Defensive Counter-Air (DCA), and in extreme cases, Offensive Counter-Air (OCA), both of which fall under the Air Force Aerospace Control (AFAC) heading. In a distant third, we find strategic attack — the least likely scenario.

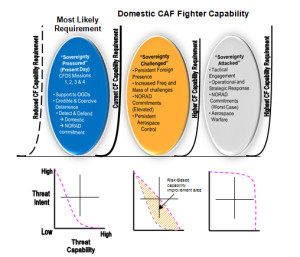

Arctic patrol and DCA are projected to make up more than three quarters of the CF-18’s projected missions (80%) over the next 30 years, which means that the next fighter will ideally be an interceptor with a life-cycle of 30 or more years. This would require a service life of 9,000 hours, at least, based on the current 300 hours per year used to measure CF-18 usage.

Given the government’s commitment to a strong presence in the Arctic, it has been mentioned many times that two-engines would be the preferred configuration. This is something I strongly agree with.

If a pilot ends up losing the engine on a single-engine fighter over the Beaufort Sea (or anywhere north of the tree line in the Arctic) he/she will be left piloting a lawn dart. Even in the event of a safe ejection, the chances of survival are slim-to-none. A pilot in command of a twin-engine aircraft, however, could limp it back to one of our Arctic airbases, as the chance of losing both engines is minuscule.

The counter-argument to this is reliability. If you have a well-built, reliable engine in your single-engine fighter, what is there to worry about?

Unfortunately, all it takes is one event for a pilot to lose his/her life. Having two engines gives you one more possibility, and there is no way around that. It may be the more expensive option, but at what point does saving dollars trump protecting the lives of our servicemen and women?

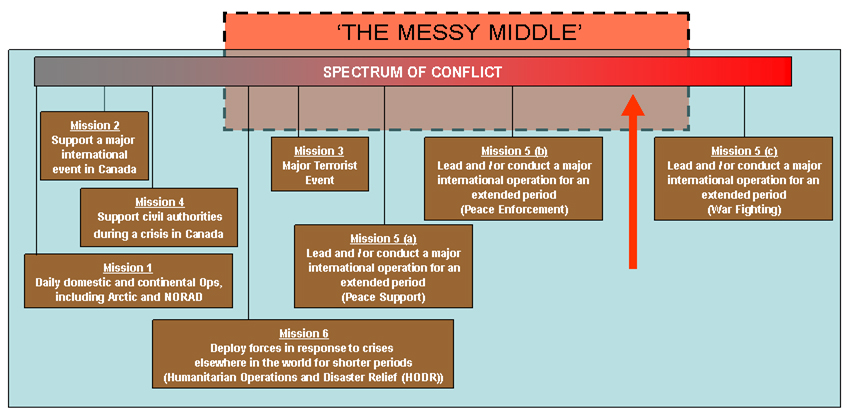

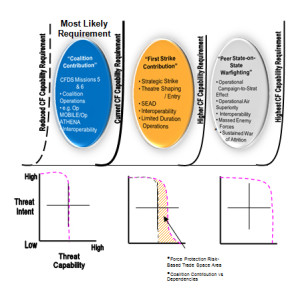

That pretty well sums up the non-discretionary roles. As far as expeditionary and NATO operations, Canada’s roles are discretionary and the likelihood of engaging in first-strike warfare is low.

As a result, we don’t need as much emphasis on items like stealth and suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) capabilities, but we do want an aircraft that is at least capable of supporting bombing efforts… and that means good range and decent payload.

By now, you have an idea of the Canadian Armed Forces spectrum of combat as a whole. The need for a first-strike stealth fighter with secondary interceptor capabilities is pretty well non-existent.

One other consideration I haven’t seen much public discussion around is manufacturing and sharing technology. Lockheed Martin has already partnered with Canadian aerospace firms to manufacture components for the F-35, but all assembly (if Canada moves ahead with the procurement of the aircraft) is completed at the company’s facility in Fort Worth, Texas. Furthermore, American laws prohibit sharing the F-35’s most sophisticated systems; Canada will be able to use the aircraft… but the technology that makes it work will remain a mystery.

Canada could do better in this regard. Eurofighter and Dassault have both reportedly offered full assembly in Canada along with tech-sharing and the freedom to modify the aircraft and update independently of both. If we took that approach, Canada could modify the electronic or propulsion systems as required, creating an aircraft that meets our country’s specific needs.

These things will be covered in more detail over the remaining five parts of this series. Part Two will look at the Boeing F/A-18E, F ‘Super Hornet’, and Growler.

Comments are closed.