It was preceded by the misnamed Canadian Aviation Corps (actually just one aircraft, two pilots and one mechanic), by Canadians serving in the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in the First World War, by the short-lived Canadian Air Force in England in 1919, and by the home-based Canadian Air Force of 1920-24.

As early as 1917, then Lieutenant-Colonel Redford (LCol) “Red” Henry Mulock, the first Canadian ace in the First World War and later the highest-ranking Canadian airman of that war, had nearly convinced the Minister of Militia that an independent Canadian air force should be formed.

Mulock’s writings on the formation of an independent Canadian Air Force revealed his vision, intelligence and a ready grasp of the problems inherent in the formation of a Canadian flying service. His arguments were based on technical knowledge, operational experience, and sound judgment. Mulock carefully outlined a proposed composition for basic flying units, using as his model the organization of the RFC, rather than that of his own service, the RNAS. With force and clarity, he emphasized that the key to an understanding of the organization was the principle of specialization of function. The distinct tasks of fighting, reconnaissance, photography, artillery co-operation, bombing, close support of ground forces, and balloon observation required distinct units, distinct tactics and training, and specialized aircraft. By these functions, squadrons would be grouped into a brigade, consisting of two wings. Mulock argued for the creation of at least a full brigade of at least eight squadrons together with an air staff, supply and equipment detachments, plus a kite balloon establishment that together made up the range of functions to be carried out by a Canadian RFC-like air brigade.

On May 17, 1917, LCol Mulock made a presentation to the Canadian Cabinet with his proposal along with other administrative details for the formation of an independent Canadian Air Force. On May 30, when the Cabinet delivered its judgment on the future of Canadian military aviation, there was disappointment; nothing was to be done in this regard.

Mulock and the others involved were discouraged but this was not to be the end of Mulock’s efforts in trying to form an independent Air Service for Canada. Mulock had finished the war as a distinguished airman with the newly formed Royal Air Force. In this new service, he had been tasked with forming the No. 27 Group, a special force consisting of two wings of huge four-engine Handley Page V1500 bombers, designed to strike deep into Germany from bases in the UK. By November, Mulock had his squadrons ready to bomb Berlin, but the war ended and 27 Group stood down.

In March 1919, Colonel Mulock, now the provisional commander of the new Canadian Air Force in England, provided another recommendation paper to the Canadian government on a post-war “Aerial Expansion – With Particular Reference to Canada.” Mulock’s covering paper was four pages and included two appendices, which provided the suggested organizational construct and the potential expenses involved. His paper covered two primary aspects: the control and regulation of all aviation by legislation and the provision and operation of aircraft for naval, military and other government services.

In regards to those operations, he stated:

“ …it is unlikely that Canada will need to provide a large force in the time of peace but none the less as the wars of the future will be largely wars of the air, and, as in consequence the first blow struck will be almost coincident with the declaration of war, some form of national aerial defence will undoubtedly be necessary.

It must be remembered that while in the past aircraft have been almost exclusively employed as adjuncts to the Army and Navy, in the wars in the future there will definite and unsupported aerial conflict by large formations of machines.

This will introduce a completely new art of aerial strategy, as different in its application from either Naval or Military as these two are different from each other.

While therefore, it will still be necessary in the future to provide aircraft to operate as auxiliaries to the Naval and Military Forces, the great bulk will carry on an individual campaign involving lines of action quite unconnected with either the land or seas campaign.

The country therefore must provide an organization to deal with and control the forces employed on this new method of warfare, and she may do this either by maintaining three services, i.e.

(a) The direct or Independent Air Service;

(b) The Naval Air Service;

(c) The Military Air Service;

or by combining all three as one Air Force.

From the point of view of efficiency there is no doubt that this latter method is the best, since it secures unified control and [a] unified system, and moreover, allows for the immediate transfer of Units to the point of pressure…Although the adoption of one force under one control and the placing of this control in the hands of the same bureau which is responsible for the legislative side involves a new Department and service of the State, the direct benefits to the Dominion itself, and to the whole Empire, are very great. By adopting an arrangement already in force in Great Britain, Imperial Standardization will be made for and by constant exchange of personnel and the closest liaison of all technical matters, the carrying on of war of defence on either side of the Atlantic would be enormously simplified.”

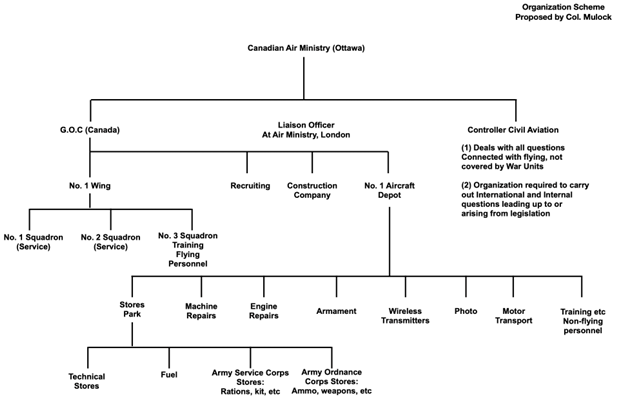

The organizational construct he proposed in an appendix to his paper looked like this:

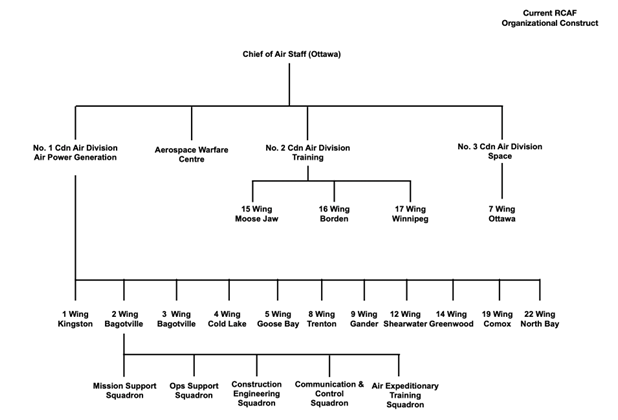

Current RCAF Organizational Construct:

The accompanying notes to this appendix further indicated that “this scheme of organization may be enlarged without interfering with Administrations, Control or Operations to any sized Air Force.”

While the Canadian Air Force in England in 1919 would end up being very short-lived, Mulock’s paper laid the foundation for a discussion of “airpower” in Canada. And, although the path has been somewhat tortuous in getting there, we have achieved that in the RCAF of today, which has a unified command system and that is simultaneously operationally flexible, allowing for the employment of forces in support of land or naval operations, in support of coalition forces and / or in support of unique air defence or air sovereignty missions.

Mulock would surely recognize both the organization construct and components of today’s RCAF. He would understand the divisional and wing structure from his own 1917 proposal. And although he might not have understood the precise technology of the future, he would have recognized the functions provided by those technologies; his kite balloon establishment being replaced by a space division and space wing for largely the same purposes. He would appreciate that the RCAF provides aircraft to support the naval and land forces while also independently carrying out other operations involving lines of action quite unconnected with either.

The functions he noted in his own appendix as the Construction Company and No. 1 Aircraft Depot are embedded primarily in 2 Wing Bagotville and he would certainly understand the function of the current No. 2 Canadian Air Division and its training mandate. In terms of fighter, trainer, transport and search and rescue and tactical land and / or maritime aviation support, all of these lines of operation would be familiar to Mulock. Perhaps, given his own personal experiences as a Group commander at the end of the First World War, the only thing missing from the current functions is the lack of a strategic bombing / attack capability although one might argue that the recently announced acquisition of an armed Remotely Piloted Air System might be able to perform this very function.

And more importantly, he would also fully recognize the professionalism, skills and dedication of the men and women in today’s RCAF. He would even recognize the current motto of the RCAF “Sic Itur Ad Astra” / “Such is the pathway to the stars”.

Colonel Redford H. Mulock was definitely a visionary, and he would be proud of the current RCAF and its capabilities. In his own era, as early as 1915, Mulock had been Mentioned in Dispatches (MID) for gallantry or otherwise commendable service as a fighter pilot. He was both the first Canadian ace to destroy five enemy aircraft, as well as the first RNAS pilot to achieve that distinction. For his outstanding performance, in June 1916, Mulock was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). After the war, for his overall outstanding wartime service, he was appointed as a Commander of the British Empire (CBE), the only Canadian airman to receive that honour. When Mulock left the military, he became involved in the peacetime aircraft industry. Nevertheless, he re-enrolled in the RCAF Reserve rising to the rank of Air Commodore, later becoming an Honourary Aide-de-Camp to two Governors-General. “Red” Mulock died in Montreal on January 23, 1961. He was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame on June 10, 2010.