By Jeffrey D. Rodney

On October 22, 2014, a lone gunman shot ceremonial guard Corporal Nathan Cirillo at the National War Memorial in Ottawa. A few minutes later, the gunman opened fire inside the Centre Block on Parliament Hill. He was gunned down before killing anyone else.

According to an Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) report released a few months later, the RCMP missed an opportunity to stop the gunman before he entered Parliament because a radioed warning of his approach came out garbled. This was one of many deficiencies outlined in the report. The OPP concluded that the shooting was a “grim reminder that Canada is ill-prepared to prevent and respond to such attacks.”

On September 30, 2017, a man rammed and stabbed a police officer in Edmonton, before ploughing into four pedestrians with a truck. The incident was evocative of the deadly attacks committed with vehicles earlier this year in London, Barcelona, and elsewhere. These events have reinforced the fact that the security threats facing nations and the organizations protecting them have become more complex and dynamic than ever before. Global megatrends are only exacerbating these challenges.

To keep nations secure, governments around the world must transform themselves to create more agile and effective approaches to security. Nations need to be taking a holistic, ecosystem approach to assessing their capabilities.

The Security Ecosystem

Every nation is protected by a broad array of individuals and organizations that form its national security ecosystem(SEAM). This ecosystem consists of multiple functional elements that must seamlessly collaborate and coordinate to address today’s security challenges. National security ecosystems commonly include defence, intelligence, law enforcement, criminal justice, border and immigration control, critical infrastructure protection, emergency response and public health management. To be fully effective, these functional elements must interact, interoperate, and collaborate to mitigate risks and maintain security. In addition to these many inter-functional relationships and interactions, a certain level of national coordination is also critical.

To reduce vulnerabilities, nations must take a systematic look at their organizational structure, to close the gaps and strengthen the seams between agencies and functional areas.

General John R. Allen is a retired general of the U.S. Marine Corps and Senior Strategic Advisor to PwC’s Public Sector practice. In his work as Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL under former president Barack Obama, he observed the problem of foreign fighters returning to their home countries and becoming easy targets for radicalization. “In watching events unfold, it became apparent that many of these host countries had substantial seams between ministries and principal agencies, and gaps in capabilities, affecting their ability to respond,” said Gen. Allen. Enclaves of at-risk Muslim populations, such as Molenbeek in the municipality of Brussels, became “no-go zones.” In an environment of organizational dysfunction, these no-go zones become support zones and launch pads for radicalization.

Learn more about the Security Ecosystem Assessment Map (SEAM) on video by clicking on the image below, or go here.

To remedy these deficiencies, countries can begin with a comprehensive analysis of their organization “left of boom”—originally a military term referring to the timeline before an explosion and more recently described the military’s effort to disrupt insurgent cells before they can build and plant bombs. There are also a number of questions they can ask to evaluate their effectiveness during and after an event occurs.

Left of boom: Are we methodically looking at how we’re organized? Are the entities responsible for collecting and analyzing information sharing it with all those who need that information in order to prepare and respond? For example, an intelligence agency might have clearly identified someone as a potential threat, but that information might not have been communicated to police. Is there commonality across IT systems, are databases protected, is the information available across the security ecosystem?

At the boom: Are first-responders adequately equipped and trained to deal with an event? Do the various types of responders (police, SWAT team, etc.) have compatible communications equipment? How is the response coordinated locally, regionally and nationally? For example, what if a crisis occurs in several places simultaneously? How well are we exercising all of our systems associated with various events, from a single attacker in a shopping mall to coordinated attacks on our transportation systems in multiple locations?

Right of boom: This is about consequence management. It includes search and rescue capabilities, the ability to provide medical support for mass casualties, and longer-term aspects such as reclaiming and rebuilding neighbourhoods.

Countries have to take measures to objectively inventory their capabilities and conduct an organizational analysis on how their ministries and entities communicate, coordinate, and collaborate. It is a continuous process; there is never a point where you can stop analyzing your organizational approach to make sure the seams and gaps are closed, and stay closed.

At the same time, more effort is required upstream to assess and understand at-risk populations. “One problem we consistently find is our inability to grasp the factors that are radicalizing youth,” says Gen. Allen. “Countries have not moved far enough upstream to assess the sources and means of radicalization. When was the person who became an extremist or terrorist radicalized, how long did it take, what were the principal factors? These answers are really important for understanding how to reduce hot-spots of extremist activity. We need to conduct systematic community outreach and work in close partnership with community leaders to reduce these vulnerabilities.”

In addition to these immediate, on-the-ground issues, global megatrends can be expected to further exacerbate current security challenges.

Global Megatrends

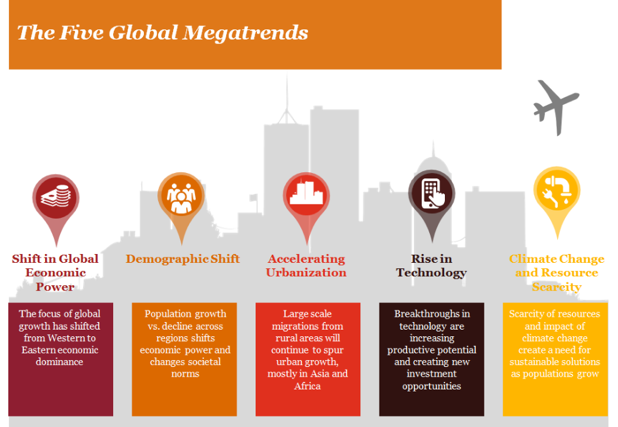

“Global megatrends are driving defence and security vulnerabilities that are almost all non-country specific,” says Thomas Modly, PwC’s Global Government Defence Network Leader. He notes that Western democracies are all facing similar types of challenges. “They have diverse populations, they face decentralization of the threat, and technology is enabling individuals and very small groups to do highly disruptive and destructive things that they couldn’t have done twenty years ago.”

These megatrends—macroeconomic and geostrategic forces that are shaping our world—present both tremendous opportunities to seize and extremely dangerous risks to mitigate. While they may affect different countries in different ways, depending on each nation’s own institutional and structural strengths and weaknesses, the following five megatrends have major implications for global defence and security.

- Shift in global economic power. The focus of global growth has shifted from Western to Eastern economic dominance. Pacific trade routes are becoming increasingly relevant. China’s transition to a global power projector will challenge the traditional balance of forces in the region. More and more North Korea presents a disruptive potential. And the capacity of Western nations to exert influence is declining.

- Demographic shifts. Explosive population growth in some areas against declines in others contributes to everything from shifts in economic power to resource scarcity to changes in societal norms. The youth bulge—the rapidly growing demographic group of young men and women in developing nations with limited economic opportunities, access to education, and safety—is creating significant security challenges as these conditions breed social discontent, crime, violence, and susceptibility to radical ideologies and movements.

- Accelerating urbanization. The UN projects that by 2030, 60 percent of the global population will live in cities, and one in three people will live in cities with at least half a million inhabitants. In 2016, there were 31 “megacities” (cities with more than 10 million inhabitants) and that number is projected to rise to 41 by 2030. However, mass migration to cities that are unable to expand infrastructure and ill-equipped to provide even basic services to such large numbers can result in the development of “mega slums” and “feral cities.” Already there are examples of megacities where police and security forces dare not tread. These “ungovernable” spaces (where networks and criminals operate beyond the writ of municipal government) can become incubators for the radicalization of whole segments of the population and breeding grounds for criminal networks, terrorist non-state actors, and others who wish to disrupt security and stability.

- Rise of technology. While breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and other frontiers are improving productive potential for commercial enterprises, they are also enabling bad actors to advance their own capacity for disruption and destruction. And while technologically advanced countries can benefit from technology to enhance their intelligence-gathering and surveillance capabilities, our dependency on technology (the Internet, cloud computing, encrypted network-capable devices, electrical grids, automated supply chains, etc.) increases our vulnerability by giving non-state actors or well-organized criminal networks the capacity to attack at the heart of our societies.

- Climate change and resource scarcity. The recent hurricanes that wreaked devastation on Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico and several other Caribbean islands were just one example of the forecasted increase in the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events. Greater use of defence forces as first-responders for such natural disasters will put more strain on military resources. As global population increases and natural resources become scarcer, disputes over water and fishing rights will intensify. And as storm surge intensity and sea-level rise begin to affect coastal cities, larger infrastructure investments will be needed to ensure the population’s physical safety, and mass evacuations may be required.

A Systematic Approach

Nations should develop strategies that consider both fronts: potential immediate threats, and the more longer-term but inevitable threats engendered by megatrends.

Gen. Allen expects these trends to worsen as more success is seen in the destruction of ISIL (fragmentation and dispersal of the threat), and as the unresolved political situation in Syria continues, generating thousands and thousands more refugees.

Countries should not be tentative in inventorying the relationships among their organizations and agencies that should be working together. Sometimes just a few internal organizational changes can reduce vulnerabilities and hamper the capacity of bad actors to take advantage of the seams between organizations and the gaps in capabilities.

This type of inventory should consider the organizational, intra-functional, inter-functional and national dimensions of the security ecosystem.

- The organizational dimension focuses on the maturity, capacity, capabilities and efficacy of the individual entities within each of the relevant national security functions.

- The intra-functional dimension focuses on the maturity, capacity, capabilities, collaboration and functional efficacy among entities within each relevant national security function.

- The inter-functional dimension focuses on the maturity, capabilities, capacity, collaboration and functional efficacy among entities responsible for all the relevant national security functions.

- The national dimension focuses on the maturity, capacity, and efficacy of ecosystem coordination at the national level.

“Individual agencies in government may have a decent understanding of what their individual deficiencies are, but often these deficiencies are only a part of broader, system-wide weaknesses that can’t be solved in isolation,” explains Thomas Modly. “The more a nation goes through this process of taking a system-wide approach, the more the different players involved will accept it, and the more they will become accustomed to working together to develop a more agile and effective prevention and response capability.”

The threats to security are multi-faceted and continually evolving. Only by conducting a systematic analysis of the relationships among all components of your security ecosystem can you identify the vulnerabilities, and then work to close the seams.

Jeffrey D. Rodney is a Director, Consulting & Deals — Government Defence at PwC.