Managers strive to maintain balance every day, along with time.

Management, leadership, and teamwork (Courtesy Pixabay & Ian Mack)

7 November is this year’s International Project Management Day (the first Thursday in November annually).

It is not a day much highlighted within Canada, yet their construction associations alone suggest there are over 450 major projects underway at this time. The Project Management Institute (PMI) estimate the there are between 8 million and 11 million project managers (PM’s) in North America, and Canada projects growth by an additional 90,000 in the next 5 years. Nevertheless, the existence of the day begs the question, why should we care?

Project management has been practiced for centuries, as indicated by such wonders of the World as the great Pyramid of Giza. Modern project management is generally agreed to have become an accepted and unique discipline since the 1950s – one that has continually evolved to meet the growing complexity of endeavours and emerging technologies.

Yet, the statistics are disturbing. Despite the efforts of organizations to spend as much as 20% of a complex project’s budget on project management and the growth of certification associations, up to 70% repeatedly fail to meet expectations.

Noting that VANGUARD serves the Canadian defence and security industries, it is appropriate to focus on project management for military acquisitions. My experience in Canada’s Department of National Defence (DND) spanned the decade 2007-2017 with a portfolio of billion-dollar complex weapon system platform acquisitions responding to Canadian Army and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) requirements. Throughout and since, media reporting followed two themes: the continual critiquing of the government’s highly complex procurement system and assessed degree of failure of such projects to be delivered in a timely and affordable manner.

Aside from the well documented shortfalls of the military procurement system, much of the criticism has fallen on the shoulders of those charged with project management and led by PM’s employed in DND. Project management in government has been defined as ‘the systematic planning, organizing, and monitoring of allocated resources to accomplish identified project objectives and outcomes. Clearly, those engaged in project management and PM’s in particular are responsible for the outcomes.

Structurally, military project management occurs in two phases. The first phase is led within government until contracts are approved for award. The second phase is led by industry once contracts are awarded, but with their performance constrained by Requests for Proposals (RFP’s) but enabled and closely monitored by the project management teams in DND.

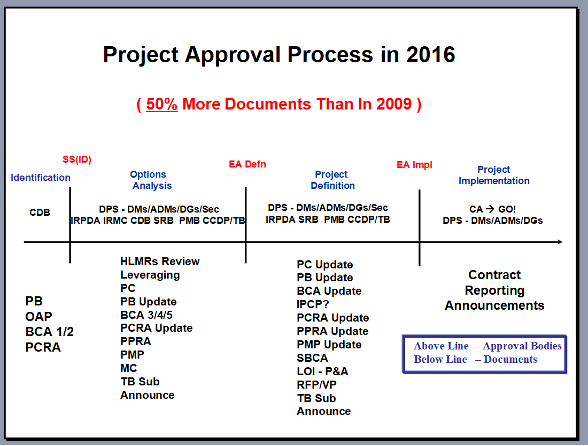

Much has been written about the ‘broken military procurement system’ – its lack of accountability and questionable governance, the shortage of personnel with the needed project management skills and business acumen, the lack of transparency, and the risk aversion that has continuously layered more and more processes on the procurement system (Figure Two) while avoiding meaningful innovation. In essence, DND PM’s and their Project Office Teams are charged with advancing highly complex projects through an ever more complex acquisition and procurement approval system.

stakeholders and generating copious approval documents (Courtesy Ian Mack)

A typical Project Office team is led by a PM (sometimes accompanied by a Deputy PM) and includes a project control office, an engineering team, an integrated logistics and support team, a procurement and finance cell, and a supplier liaison section (on-site with the Prime Contractor). For RCN projects, an Operational Requirements Manager is also onboard. There is a preference for the heads of section to be as qualified as the PM, but this was rare in my projects. Unique to the Canadian government, two other functions are carried out by separate government departments, functions which in most government project management systems would work for the PM. Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) provides contracting and related procurement services, and the industrial and technological benefits (ITB’s) are provided by Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada (ISEDC).

The PM’s responsibilities are laid out within each Project Charter. While definitions of their responsibilities vary across organizations, PM’s generally lead a team to organize, plan, and execute projects while working within assigned constraints (e.g. policies, operational requirements, budget, and schedule) and resources – resources also including in Canada’s case those in different departments assigned as contract and ITB managers, and of course the prime contractor.

DND PM’s are thus responsible for government planning and coordinating of the necessary activities to advance projects from the operational requirement definition stage through to delivery of the equipment, establishment of the in-service support system and subsequent project closeout. This includes being the lead risk manager responsible for addressing disruptions and barriers to executing projects successfully over many years or even decades.

PM’s must be highly skilled at both management and leadership to ensure that a myriad of stakeholders remain aligned as the project deals with many overwhelming challenges – challenges that regularly disrupt planned schedules and routinely include unforeseeable emerging risks that often include a lack of collaboration among key stakeholders. Most experienced PM’s believe that ‘schedule is king’ in high performing projects, and thus DND PM’s encourage a high degree of urgency every day. From my experience, that hackneyed saying ‘herding cats’ comes to mind, and as one retired Assistant Deputy Minister of Materiel was fond of saying, “projects slip one day at a time.”

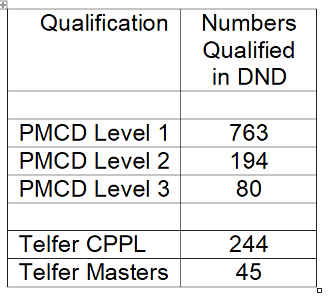

To address the project management challenges within DND, a Project Management Competency Development (PMCD) program was established by the Director of the Project Management Support Office (DPMSO) in response to the Canada First Defence Strategy of 2010. PMCD qualifies personnel to three levels of competency and is open to the three Groups conducting project management in DND (see Figure Three). The PMCD has apparently been adopted as a template by the Treasury Board (TB) use across government. DPMSO strives to maintain links to professional associations such as PMI headquartered in the USA and the International Centre for Complex Project Management in Australia. Other organizations that produce useful benchmarks are the International Project Management Institute with headquarters in Geneva (the Canadian Chapter being the Project Management Association of Canada) and the Major Projects Association in the UK.

Personnel as of Oct 2024

The Canadian School of the Public Service (CSPS) also offers project management courses for the broader Public Service – some dozen on-line self-paced short courses largely based on critical project activities as defined by PMI’s Project Management Basic Body of Knowledge, but these lack treatment of emerging techniques to navigate complex projects. However, the Telfer School of Management at the University of Ottawa offers educational options tailored to government complex projects, including an MBA option and a certificate in Complex Project and Procurement Leadership (CPPL).

Project management policy resides with the TB under the leadership of the Comptroller General. However, the TB analysts of DND’s major projects during my tenure (ending in 2017) typically had no experience and minimal knowledge of complex project management. Furthermore, and as with CSPS, TB policies catered only to the most common projects across government, not those that are complex. A related concern is a recent recommendation published by Policy Options in late September 2024 to authorize TB with “the power to pause or terminate procurements and technology projects that have gone off the rails”. Clearly, interventions of this magnitude would render TB partially responsible for the resulting project outcomes despite the lack of any significant degree of relevant knowledge and introduce one more barrier requiring PM’s to navigate.

I started this article by asking why we should care about International Project Management Day. I would offer that:

- Project management in DND is critical to equipping the Canadian Armed Forces to survive when in harm’s way.

- It is worthy of much greater investment to prepare all involved in the practice of project management, from DND, PSPC and ISEDC to senior governance and TB.

- PM’s are significantly responsible and thus accountable for very complex and expensive weapon system platform acquisitions, but the perceived failure of such projects does not make them automatically culpable.

Based on 17 PM’s I worked with, I observed accountability, dedication, courage, perseverance, and situational leadership as they worked 60–80-hour weeks. Those projects were delivered as a testament to PM’s in government and in industry.

Therefore, we should be celebrating those involved in project management of major equipment acquisitions. We should not be publicly shaming their projects (and by extension those executing such complex projects), as PM’s and their teams execute complex projects, in a very complex and demanding government bureaucracy, and as their projects are buffeted by a broader complex and interconnected world best described as exhibiting compounding polycrises.

On 7 November, I invite every media outlet and defence consulting company to select and showcase a team engaged in the project management of weapon systems projects in government and in industry.