The Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) acquisition project is under contract since 2018 to conduct design work leading to the delivery of 15 frigates to replace the capabilities that existed in the three Tribal Class destroyers (now retired) and the 12 Canadian Patrol frigates (modernized in the last decade). As the CSC’s start to take shape it is not surprising that Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office and Office of the Auditor General are both planning to release reports in 2021. I also note some recent articles on the CSC project that cause me concern in terms of the conclusions reached.

It, therefore, appears timely to look back at how CSC has arrived at this moment by offering a perspective from the experience of one that was involved – and many would say one who at least shares the accountability for the current state of affairs.

NSPS and CSC

The National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS, now known as the National Shipbuilding Strategy – NSS) was initiated in 2008, announced in 2010, and entered implementation in early 2012. The intent was to address the boom-and-bust cycle of Federal fleet construction which had by 2008 led to considerable atrophy of Canada’s large ship construction capabilities. The adopted methodology was similar to that used by many allies in terms of establishing strategic relationships with selected Canadian shipyards (initially two and recently modified to three).

The initial shipyard competitive sourcing of two shipyards occurred in 2011 to create sustained shipbuilding activity for 25 years or more in each. NSPS affected the CSC project by including it in what was named as the Combat package of naval shipbuilding work that was competed and won by Irving Shipbuilding Incorporated (ISI). For those interested in the details of NSPS (the good and the not so good), I refer you to a number of CGAI papers that I have written in the past.

NSPS set out to reap the benefits of a collaborative relationship with the shipyards which since 2012 has played out in many positive ways with ISI for the CSC project.

From the outset, it was understood that CSC was unique in two ways. The first was its high degree of complexity that demanded a different set of expectations and execution approaches. Secondly, it was the sole surface combatant under NSPS, with weapons and sensor systems requiring a high degree of integration that rendered the project developmental in nature. Given these peculiarities, Canada could have pursued CSC entirely outside of NSPS by running a separate competitive process in all aspects. In such a case teams would have been unrestricted in their teaming arrangements with respect to the prime contractor, designers, and shipyards. However, such an approach could have rendered NSPS non-viable having so reduced the work for ISI in the Combat package.

Canada conducted research and analysis regarding prime contractor options for CSC design and construction. It is common for shipyards to be assigned prime contractor responsibility for long production runs of ships. This is less costly than paying a separate prime contractor for many years after the first ships had been delivered and also avoids the ‘thin prime’ model which is often problematic. Canada selected the shipyard prime contractor model and negotiated a related agreement with ISI – such agreement contingent on contracts being awarded and the shipyard meeting a defined target state in terms of prescribed practices to yield the desired level of productivity.

Requirements

The Statement of Requirements (SoR) for a warship that will be in service for at least 30 years is always a daunting task. The continuous evolution of new technologies and threats leads to a new weapon and sensor systems which the SoR must try to take into account. The SoR also identifies a nation’s unique requirements which include such things as the roles to be performed and more tactical matters such as regulatory and operating protocols. From these, the ‘high-level mandatory requirements’ (HLMRs) are established. I can attest to the years of work that was invested in the CSC SoR.

Because of the nation’s unique requirements, any off-the-shelf design will have to be modified and integrated into the selected platform. And because of the evolving threats weapon and sensor performance requirements must be defined with ‘legs’. If such requirements can be met by equipment already in service, one might procure a system likely to be obsolete long before the last ship is built 20 years after contract award and well after the first of the class was delivered. Alternatively, when the SoR sets performance standards requiring further development, care must be taken in the degree of equipment system development costs and risks that accrue. RFPs routinely quote a Technical Readiness Level (TRL) protocol with mature systems being ‘9’ on a scale of 1 to 9. As a data point in the CPF project, many Canadian systems were selected that were rated at low TRL levels yet most delivered successfully. However, it is more common for systems to be required with TRL6/7 from manufacturers with a record of delivering effective systems on time.

Given the extensive work done on CSC requirements, the SoR remained designated as ‘preliminary’ for an extended period of time. An initial requirement reconciliation activity occurred based on assistance from ISI in identifying companies to conduct a comprehensive review and in contracting two reputable companies to execute an independent analysis. That work led to refinements of the HLMRs in the SoR which enabled consideration of an improved procurement plan. The amended SOR was then integrated into the Statement of Work for the RFP with detailed technical performance and evidentiary deliverables defined for all requirements as captured in a prioritization scheme.

For the CSC project which selected the proposed design based on the Type 26, one would expect that the bidder did their design assessments of modifications required to meet RFP priority requirements in a compressed timeframe between RFP release and bid submission. Hence the nuances in terms of the broader impacts to existing systems and cost/schedule risks would only be apparent during a more detailed design process after selection and contract award. For example, in the case of the selected Type 26 parent design, options available from Australia’s Hunter Class modified Type 26 design could adequately meet Canadian requirements and at reduced risks. Such considerations argued during RFP development for the need for a requirements reconciliation activity once a preferred bidder’s proposal had been selected.

In terms of the CSC’s post-contract award requirements reconciliation, any proposal to replace as-bid equipment must respect the integrity of the competitive procurement process such that subsequent equipment system replacements would not materially change (or be seen to change) the results of the Bid Evaluation process.

One should note that such decisions do not change the SoR which was the Royal Canadian Navy’s stated requirement set that shaped the RFP, against which requirements reconciliation options would be measured and by which the modified frigates would be assessed for performance during the trials program. However, the SOR is likely to change over time to address emergent technologies and threats by the time the 15th CSC plan is in play around the mid-2030s, some 20 years since the SOR was set for the 2016 RFP.

Procurement Process Attributes

Once industry has been engaged every procurement process obtains approval for a procurement strategy and plan. The initially approved CSC procurement approach was a best-of-breed approach entitled the ‘most competitive procurement’ strategy. It consisted of running two competitive processes, one to pick a warship designer and one to pick a combat systems integrator. Once selected these two entities would be responsible for completing each of the equipment and systems. In essence, this was a ‘clean sheet of paper’ design that maximized competition, but which might have been ten years in the design phase with the attendant significant risk.

After the initial requirements reconciliation, it was obvious that a number of existing warship designs exhibited the refined HLMRs in the SoR, this being a change of consequence. It enabled the selection of a modified military off-the-shelf methodology entitled the ‘most qualified team’ procurement strategy and employed commonly with our allies. It would preserve the advantages of competition while enabling schedule and cost-saving opportunities at reduced risk.

With ISI pre-selected as the prime contractor and in keeping with the intended strategic and collaborative relationship, the RFP was jointly developed by Canada and the shipyard. The effort required to reach an agreed RFP for issue by ISI was onerous but offered benefits as well. As an example, this was very evident in addressing a perennially challenging contractual term – intellectual property (IP). CSC was no different than other platform acquisitions in that Canada wished to maximize IP rights for itself while industry wishes to restrict the offer of the broad use of their IP. Furthermore, for existing ship designs IP rights were already negotiated for many equipment systems creating a reluctance to reopen expensive negotiations during competition. Here as in many other areas, ISI’s input was important in bringing a commercial perspective to what could realistically be expected.

The resulting solicitation process was required to respect all contracting principles of Canada and netted three comprehensive bids. The bid evaluation was then conducted by Canada with ISI providing input for consideration. The final selection of the preferred bidder employed Canada’s standard review and approval processes. As is the norm the equipment systems (and their suppliers) as identified in the winning bid complied collectively with the prescribed Industrial and Technical Benefits (ITB) requirements of the RFP. In CSC, the ITB value proposition carried significant weight in the evaluation.

As often happens, some capable Canadian companies appear to have not been part of the selected bidder’s proposal, causing them to make representation to Canada after the fact for consideration. Unlike some other nations, Canada has no Maritime Industrial Strategy defining which Canadian companies to favour or direct in the CSC procurement process. When strong companies miss such once in a generation opportunity with potential challenges to future market share, I am indeed empathetic. But in cases like the CSC project where after the fact exceptions might be made to replace foreign as-bid equipment systems with Canadian products, I also understand the potential for legal challenges. I can say that the CSC RFP employed a tailored requirement developed in accordance with the policies of Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada (ISEDC) which continually strives to improve its policies and execution. I also can attest to the very significant effort expended to ensure the RFP provided as much motivation as possible for bidders to select Canadian suppliers.

Transparency

Many would argue that the degree of visibility into the future CSC’s combat systems and capabilities has been wanting. Without the provision of information by the Project Office, some observers have provided perspectives based on assumptions of the selected system’s attributes. Fortunately, greater insight was recently provided in at least one published article [1] , and government information has started to flow. But without a degree of ongoing transparency, I worry that observers may make further assumptions without context and generate misleading conclusions that could harm the credibility of the CSC project.

There are challenges to being transparent and in being seen to be transparent. The subject matter is exceptionally complex and difficult for laymen to understand. Much of the information will be dynamic as risks routinely emerge (many known-unknowns with a smattering of unknown-unknowns), causing observers to doubt the veracity of what is released when it subsequently changes. It is also important to recognize the degree of commercial sensitivity and corporate confidentiality implicated at key project inflection points. And with many observers inclined not to trust the information available without the detailed evidence that cannot be disclosed, there understandably will continue to be publicly proclaimed concerns.

Nevertheless, having finally managed to clear the mandatory silence period between RFP release and the announcement of the preferred bidder plus the post-contract award requirements reconciliation, I am pleased to see the released information on the presently intended CSC’s weapons and sensor systems. Hopefully, this will now set a trend for the CSC project of periodic reports which will expose the key Canadian company products with the anticipated and achieved dollar value and jobs created, along with project status and challenges faced. CSC is too big a project to remain behind the curtain, prompting some observers to generate assumption-based opinion pieces assuming the worst and damaging the public’s trust.

Benchmarking

I am starting to see more articles being published that raise concerns about the CSC project based on benchmarking, a tool commonly employed by observers and organizations everywhere when attempting to understand whether endeavours are on the right path.

Finding comparisons that match the CSC project and are seen to be of a high quality are not only important to any benchmarking but difficult to identify. While the desire to compare CSC with similar foreign procurements is understood, it is fraught with challenges. But it does enrich the dialogue and is welcome if for no other reason than to understand how different organizations and nations approach similar outcomes in different ways. In one CGAI paper, I provided such a comparison between the procurement processes employed in Australia and Canada in the CSC and Hunter projects respectively, both of which selected the Type 26 as the parent ship design[2].

Whereas the HLMRs may be similar among nations, the unique nation requirements can complicate comparisons. In the case of CSC, these warships must accommodate many roles within one platform which some of our allies address with two or more ship designs (e.g. USA, UK, and Australia). They also have different environmental requirements (e.g. operations in the Arctic), regulations, and protocols for conducting operations (e.g. flight operations). Some nations direct the inclusion in new platform acquisitions of major equipment systems already in their inventory or highly subsidized by governments. Only the most rigorous comparisons take such considerations into account.

But there are many other challenges in benchmarking. Such analyses often occur at an early stage where there is great uncertainty in the artefacts being compared. Cost comparisons frequently suffer from ‘apples to oranges’ figures in terms of what is included in project cost data and what is not, the impacts of different economies of scale, and the effectiveness of the working relationships between clients and suppliers. Parametric models as employed by the Parliamentary Budget Office attempt to address such considerations. However, in all cases, ship design and construction schedules dramatically affect cost estimates but are notoriously difficult to predict for warships before the first ship is actually delivered.

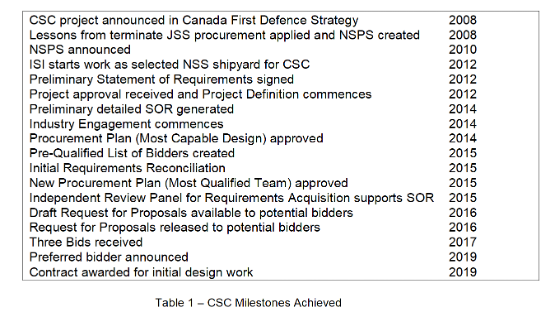

From an internal benchmarking perspective, DND has generated a scheduled target for projects to attempt to meet – two years for SoR finalization, two years to award a contract, and five years to complete delivery. Having worked diligently to get to the stage where the RFP was released on many Army and Navy weapon system platform projects, I would suggest that the application of this benchmark for Canada’s major defence acquisitions under the current processes and dispersed responsibilities is unreasonable given the levels of complexity and appropriately enhanced degree of scrutiny. To have expected CSC to achieve this 4-year standard would have been imprudent. Table 1 lays out the milestone progress for CSC. In the aforementioned CGAI paper, I demonstrate how the schedule duration to get to the competitive selection of a preferred bidder in the Australian Hunter Class project was not very different.

Nevertheless, I understand the concern that the CSC project was announced in 2008 and no ship is likely to be delivered before the mid-2020s. Delays also could introduce significant additional costs to keep the City Class Canadian Patrol Frigates in service until the first CSCs are available. And from experience, time lost cannot be made up to any great degree without introducing risk-laden disruptions or undesirable outcomes. Nor was credibility maintained by the continual announcement of delays based on premature schedule guesstimates as often required by government contract approval processes. As in the past, those charged with executing and overseeing CSC today are focused on doing everything practicably possible to avoid further delays.

So What?

The future of the RCN’s capability to meet assigned government missions is significantly vested in the CSC project. As such it is essential that the CSC project be successful in delivering capable warships. But an essential enabler is the credibility of the project over time.

This is no small task in the Canadian context which includes the perennial low opinion that many have of military procurement in general. We have seen the impact that lost credibility can have on delayed major defence projects in the past decade, on one occasion leading to outright cancellation.

I remain hopeful that the CSC Project Office will be allowed to enhance the understanding of all stakeholders including the citizens of Canada by employing timely periodic updates on project status. And for those of us on the sidelines, patience will be essential to enabling appropriate dialogue based on truth so as to avoid engaging in fiction.

This article is a condensed version of a paper published by the Canadian Global Affairs Institute (CGAI) available at the following link: https://www.cgai.ca/launching_the_canadian_surface_combatant_project

[1] Naval News, Xavier Vavasseur, 9 Nov 2020

[2] CGAI Paper, Another Way to But Frigates, Ian Mack, November 2019