After a lengthy period of the most extensive public consultation on Canadian defence in a generation, the Trudeau government released its new defence policy Strong Secure Engaged this past June. On the whole, the policy provides a surprisingly clear-eyed outline of the desired objectives for the Canadian Armed Forces and real additional resources to achieve them. If implemented successfully, the new Trudeau defence policy will fund a number of new capability investments, top up the budgets for many older projects that previously lacked adequate funding, and promises slight increases to the size of the defence team and a number of positive changes to defence human resource management.

Altogether, the new policy is quite a pleasant surprise, especially given the Liberal Party of Canada’s 2015 campaign platform and comments by Prime Minister Trudeau in the weeks before its release. Having campaigned on pledges to increase the Canadian military’s involvement in peacekeeping and reduce the budget for fighters to reallocate the money to other parts of the defence program, the additional spending for new projects is a significant departure from the campaign. The infusion of several tens of billions in additional long term funding for the defence budget is similarly surprising after the Liberal party pledged only to maintain spending, and the Prime Minister’s repeated statements that Canada’s defence contributions should not be judged on budget alone.

The new policy is underwritten by a new 20-year defence budget. As a result, there will be a modest annual increase in the defence budget of a few billion a year, but a significant injection of new funding on a cash expenditure basis. In total, the new policy provides $62.3 billion over the next two decades on a cash basis. As a result of the increase, measured on a consistent basis, the share of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product directed towards defence spending will rise from under 1 per cent to 1.2 per cent by 2024/2025.

Under Canada’s new method of calculation, which NATO has already adopted in its reports on alliance defence spending, Canada’s new defence budget math will see an additional 0.2 per cent of GDP included as defence spending, pushing our overall share to 1.4 per cent of GDP. These previously unreported items include spending by other departments for such items as payments to veterans, employee pension and benefits, the budget for the Communication Security Establishment, Information Technology support provided to DND by Shared Services Canada, Coast Guard ice-breaking in support of naval operations – these expenditures will now be included in Canada’s calculations for NATO.

This effectively serves notice to NATO that Canada officially has no intention of ever reaching the alliance’s 2 per cent of GDP spending target, nor even the commitment to produce a plan to do so by 2024. As a result of the new policy, the decline in the share of our economy devoted to defence will stop, and a progressive increase of more than 20 per cent will occur over time. In historical context, if Canada is successful in spending 1.2 per cent of GDP on defence (using a consistent method of calculation) this will bring Canada back to devoting the same share of the economy to defence as we experienced between 1999 and 2006. While the new spending brought about by this policy is meaningful, it will return Canada to the same relative level of spending experienced in Canada after a decade of post-Cold War budget cuts were completed, and before the Martin and Harper governments started a half decade of military reinvestment.

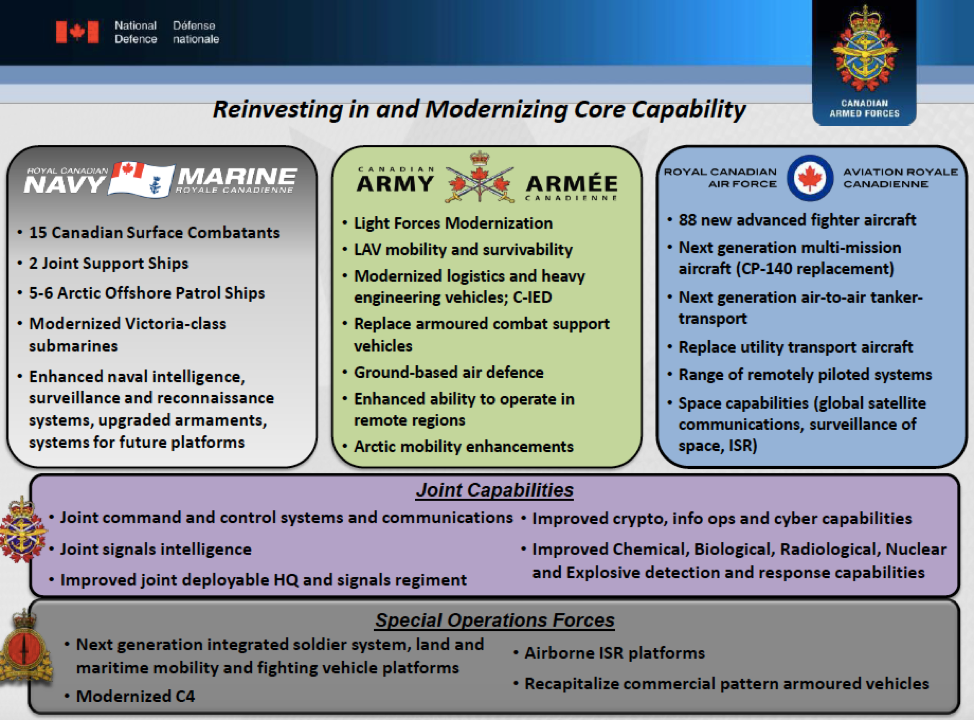

Just as important as the size of cash injection is where it is directed. Most of the new funds are earmarked for new Capital purchases. As the Minister of National Defence stated prior to the release of the new policy, a large list of Capital projects, including a number deemed critical, were unfunded when the Trudeau government formed government. On an accrual accounting basis, the new policy provides $33.8 billion in new Capital money (over the 20-year period) to fund 52 projects which previously had no funding at all.

In addition, over the life of the policy, significant funds have been reallocated within the preexisting funding envelope to provide an additional $5.9 billion (on an accrual basis) to bolster the budgets of a number of projects which already had funding, just not enough. The two biggest changes saw the budget for the Canadian Surface Combatant increase from $26.2 billion to between $56-60 billion and the Future Fighter Capability Project which saw its budget raised from $9 billion to $15-19 billion.

The increases were in part to accommodate significant official changes to the planned combat fleets for the navy and air force. The policy stipulated that Canada’s future navy will sail a fleet of 15 combatants, removing the previous ambiguity regarding how many could be obtained from a project mandated to acquire “up to 15” ships. Canada’s fighter force also saw a significant change, as the planned acquisition of new jets has risen from a fleet of 65 to 88, to deliver on the government’s policy change that Canada be able to simultaneously meet both NORAD and NATO commitments concurrently.

With respect to Capital investments, the other item of significance in the new policy is the statement that Joint C4ISR capabilities will be prioritized. While a number of such projects have been envisioned for some time, progress on some seems to have been limited by the fact that as joint projects they often lack the same type of capability champion as the core projects for the other services. Indications from departmental officials’ briefings on the new policy are that joint C4ISR projects will now receive dedicated funding sources and priority access to DND project governance to ensure that they are actually treated as priorities.

In addition to the substantive increase in Capital funding, the new policy also commits an additional $15.1 billion in operating funding, roughly $9 billion of which will go towards increasing the personnel complement of the defence team by 3,500 Regular Force, 1,500 Reserve and 1,500 civilian positions. Beyond simply increasing numbers, dozens of initiatives have been proposed to modernized multiple elements of defence human resources. There will be a major effort to diversify the forces, including bringing into official policy the target of increasing female membership in the CAF to 25 per cent. Beyond this, there will be a sweeping review of the military’s terms of service, efforts to drive enrollment times to reasonable time frames, and the creation of additional military occupations for cyber. Some of the most significant changes will affect the Reserves, with initiatives to make transfers between the Regular and Reserve forces easier. The system of Class A, B and C service will be revisited, reservists will be given an expanded list of dedicated tasks (including cyber operator, long haul truck driver, information officer) with a focus being placed on generating full-time capability from reservists’ part time service.

All of the above represent sound policy proposals that will be very difficult to implement. Given the number of substantive changes to personnel policies and massive expansion of procurement required to move the money provided, one wonders if Trudeau’s Cabinet realized just how much additional Cabinet and Treasury Board time they were signing themselves up for if they intend to execute the policy as outlined. The challenge of implementing such a broad set of defence changes, more than the back-end loaded nature of much of the spending, is likely to be the most significant problem associated with the new policy. This government had by all appearances placed its policy priorities elsewhere across government prior to the release of Strong, Secure, Engaged.

Canadians should have a good idea by early next calendar year of whether Trudeau is serious about implementing his new policy, or not. By that time, his government will need to have devoted significant time to considering and approving many of the individual initiatives contained in the new policy for them to start moving out on schedule. Let’s hope both the bureaucracy and government are taking short summer holidays so they hit the ground running this fall.

Reference:

- Due to the expected timelines, the increase to the CSC budget is relatively modest in the initial 20-year window, as the start of that build program is still at least 5 years away, and the acceptance of the first ship would not follow for several years beyond that.