By Julian Lindley-French

Canada is the country that makes NATO an alliance. Without Canada’s membership NATO would be less a community and more a huddled mass of European states under American protection. As the American world-burden becomes more onerous and the US relationship with NATO more tenuous, and as Europe itself teeters on the edge of deep insecurity and instability, the security and defence choices Canada will make matter not just to the people of Canada but to citizens across the Euro-Atlantic community.

The Canada First Defence Strategy (CFDS), first released in 2008, envisions three major roles for the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF): sufficient capabilities to meet the security challenges facing Canadian citizens and Canadian territory; cooperation with the United States in pursuit of shared defence and civil objectives; and the fulfillment of Canada’s multilateral objectives through the United Nations and NATO.

The security environment has changed beyond all recognition for the worse since 2008. Therefore, rendering international institutions credible and effective in this and future security environments, and with NATO at the fore remains a critical Canadian interest, the fulfillment of which demands Canadian investment in 21st century Canadian Armed Forces.

Hard and soft Canada: Why NATO matters in 2018

In 2018, Britain’s new 72,500-ton super-carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth together with an escort of new Astute-class nuclear attack submarines and Type 45 destroyers will come together to form a British carrier task group. They will then sail westward to Norfolk, Virginia, and arrive amidst much fanfare. Thereafter, days of dinners and ship visits will take place with a host of American politicians and opinion-leaders invited on board ‘The Mighty Queen’ to see Britain’s state-of-the-art warship which together with her sister ship HMS Prince of Wales will act as the platform for Britain’s 21st-century power projection. After leaving Norfolk the task group will sail north en route to Halifax, first escorted in the alliance by the descendants of John Paul Jones before the escort is handed over to ships of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), two navies, one commander-in-chief, one alliance. The strategic aim of the mission will be simple: to demonstrate to Americans and Canadians alike that Britain is a strategic power, values the transatlantic strategic relationship, and through NATO is invested in North American security and defence as much as North Americans are invested in European security and defence.

Canada needs NATO. Canada is a three-ocean power, and all three of these oceans are in some way contested. Not only does Canada look eastward back to the Old World, it looks north to the Arctic and westward to the Asia-Pacific region. Canada has benefitted enormously from globalization. However, the change being driven by globalization is subject to perils as well as positives.

Some in Canada might conclude that the big strategy implicit in Canada’s big strategic position can be left to its large, occasionally noisy neighbour to the south. They would be making a profound mistake. A century on from when Canadian forces played a pivotal role in the freedom of Europe, then the epicentre of 20th-century ‘globalization,’ Canada must prepare for an equally strategic and pivotal role in stabilizing and securing the world of the 21st century.

That world will be secured by a mix of hard and soft power. There is no doubt that Canada’s excellence in combining defence, diplomacy, and development (what the Dutch call the 3Ds) act as a beacon of security sophistication in a complex world resistant to fast and too often loose hard power prescriptions. Indeed, Canada’s championing of such sophistication helps invest the 3Ds with strategic legitimacy, not least in Washington.

However, Canada is also at the heart of new/old communities and groupings vital to 21st-century security in which many flags and identities will be needed across hard power alliances and coalitions. Such communities include the United Nations and its regional agencies, the Commonwealth, and on occasion the Anglosphere. Indeed, the latter two became more important with Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. However, Canada’s soft power cannot be leveraged if Ottawa invests insufficiently in the CAF. Indeed, the impact of the former depends, to a significant extent, on the credibility of the latter.

As an institution of democracies, NATO legitimizes and embeds armed force within an institutional framework that helps prevent extreme state behaviour, both in Europe and beyond. This is a critical Canadian interest. Moreover, the legitimate future use of armed force will demand new defence architectures that merge use of advanced expeditionary forces with cyber and missile defence, deep penetration intelligence, and anti-access, area-denial capabilities.

Such capabilities will in turn demand a strategic unity of purpose and effort of military capacity and sufficient capability that such forces are credible across a spectrum from peace support through hybrid warfare to deterrence and, if needs are, warfighting. Above all, they must be able to work together (interoperability). The development and aggregation of such force will only be possible through NATO. Moreover, NATO will also act as a critical coalition enabler providing the force generation and command and control standards for allies and partners alike to work together against such adversaries as IS/Daesh. Canada must not be left behind!

What is Canada doing?

The CFDS states that the Canadian Armed Forces must defend Canadians and Canadian sovereignty, contribute to the defence of North America with the United States, and contribute to international peace and security. The core missions set by CFDS which are reliant on the strategic context include, inter alia: daily domestic and continental missions, including the Arctic and through NORAD; response to a major terrorist attack; support for civil authority during crises in Canada; lead and/or conduct a major international operation for an extended period; and deploy forces worldwide as part of crisis response for shorter periods.

Sustained operations in Afghanistan revealed the gap between Canadian rhetoric and reality. CAF suffered from a lack of combat-ready personnel and a lack of specialized equipment and personnel, the need for which put pressure on allies, most notably the Americans. The conduct of the campaign also reinforced a simple Canadian strategic truism − unless Canada wishes to become an isolationist power, the utility of allies and partners to the fulfilment of Canadian security and defence objectives is vital.

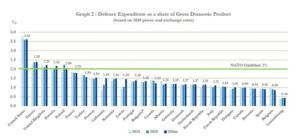

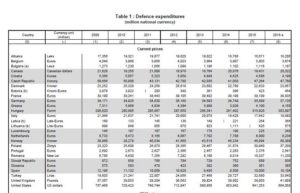

And yet, according to the CIA World Factbook in 2015 Canada spent only 1.24% of its $1.7 trillion economies on defence. Given the deteriorating strategic context of the global security environment, it is hard to see how such a low level of defence expenditure can be reconciled with the roles and missions of the CAF as stated in the CFDS, let alone future operations.

What should Canada do?

Canada is a signatory of the 2014 NATO Wales Summit Declaration which states:

Allies whose current proportion of GDP spent on defence is below this level [2% GDP on defence of which 20% must be spent on new equipment] will: halt any decline in defence expenditure; aim to increase defence expenditure in real terms as GDP grows; aim to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade with a view to meeting their NATO Capability Targets and filling NATO’s capability shortfalls.

There must be no more delusional talk from senior Canadians about how Ottawa can justify 1.24% GDP on defence because of better spending. Canada must move decisively towards 2% of GDP on defence or risk weakening NATO and free-riding on a resentful and over-stretched United States.

How can Canada do this? Leadership! The CAF have suffered disproportionately from budget reduction efforts. However, given the growth of defence budgets elsewhere in the world, given the dangers faced by the alliance, and given Canada’s unforgiving strategic environment, Ottawa must take a lead in reinvesting in the CAF. Not only will such a reinvestment help to anchor both NATO and the wider the transatlantic strategic relationship, in reality, it will also underpin Canada’s range of security tools with hard-edged military capability.

The NATO 2%-guideline is in fact only a baseline. Canada also needs to continue to reform the CAF into a deep joint force by placing the 2015 Canadian Joint Operation Command right at the core of the CAF force concept. This is precisely what the British did in the November 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) with the Joint Force Command (JFC).

How much will it cost? Over a decade Canada will need to move from spending roughly CDN $18 billion per annum on defence. A graduated increase to 2% GDP would see Canada spending CDN $34 billion by 2025.

Making Canada role in NATO more effective

Respected Canadian academic Alexander Moens writes, “Canada cannot simply go the way of specialization in terms of military capabilities. Even if niche capabilities may be sufficient in very few cases, the bulk of Canadian defence must remain based on broad defence capabilities and a wide range of action.” Canada is a hugely respected member of NATO and the wider international community. However, the CAF are too weak to serve Canada’s vital security and defence interests, for Ottawa to play the full role in the international community to which Canada aspires to play, and to make NATO work. To fill that gap Canada must rely on the strategic largesse of others. Canada must not become a free-rider! It is not the Canadian way!

Professor Julian Lindley-French is Vice-President of the Atlantic Treaty Association in Brussels, Senior Fellow of the Institute for Statecraft in London, Distinguished Visiting Research Fellow, National Defense University in Washington DC, and a Fellow with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.