After many years of writing papers to encourage real change in how Canada acquires major weapon system platforms for the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), I believe that the key points raised by Lieutenant-General (Retired) Andrew Leslie may be the signposts needed to achieve major change in how these complex procurement projects are pursued:[i]

“The current prime minister of Canada is not serious about defence. Full stop. A large number of his cabinet members are not serious about defence. Full stop.”

“Our NATO allies are despairing. Our American friends are frustrated… in private, the conversations are quite brutal.”

“I’ll say it again, the Liberal government has no intention of meeting two per cent (by 2030) and no intention of meeting 1.76 per cent (as promised in the April 2024 budget) because they rest confident in the smug knowledge that the Americans will always defend us.”

“During the run-up to the 2015 election, Andrew was asked by Trudeau, then a Liberal leadership candidate, to help craft a defence and security policy, which he did. The policy was articulated in its most detailed form in 2017, in a document called Strong, Secure and Engage… Andrew attests, ‘It promises a whole bunch of money, specific timelines for equipment, an annex of deliverables. I think there were 110 or 111, of which they’ve met almost none’.”

The General is on the money in more ways than funding for the CAF. As is well reported and witnessed in person by your author, Canada’s ability to deliver new equipment platforms to the CAF in a timely manner is not fit for purpose, regardless of the availability of funding.

Meaningful change does not seem to have occurred despite the many good intentions since 2000 of Defence policies. I say ‘does not seem to have occurred’ due to the lack of transparency as to what has occurred within the complex and risk-averse processes – something I recently wrote about.[ii]

The last major change occurred in 2014 under the Defence Procurement Strategy. It was a multifaceted strategy which I believe generally failed to “modernize or streamline the defence procurement processes” applied to major weapon system procurement initiatives. I would argue that it actually enhanced bureaucracy and ineffectiveness in the governance of such projects. Nor has it been seen by Canada’s defence industry to have been terribly beneficial, as per two data points: a specifically recommended Defense Industry data analysis organization to be funded by the government was rejected; and the Industrial and Technical Benefits policy has been seen as having failed by many in Canada’s major defence companies involved in bidding for the Canadian Surface Combatant acquisition that is perhaps the larges procurement in more than 50 years.

Nevertheless, all who have been following defence matters since 2000 recognize that intentions to improve the end-to-end processes from requirement identification to weapon system platform commissioning have not emerged. This conclusion renders the requirement to meet the NATO target of at least 2% of GDP moot because it consistently damages the argument for additional funding as illogical.

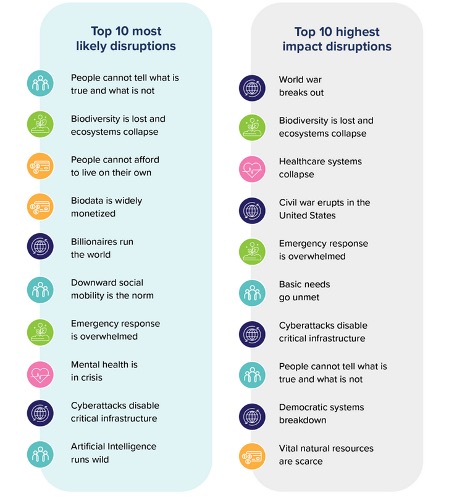

Disruptions On the Horizon 2024 Report

Top 10 Disruptions by Likelihood and Impact

Policy Horizons Canada, May 2024

Furthermore, at this time in history, expectations must be managed. The nation finds itself deep in debt with economic growth not expected to be significant for many years. And the complexities our leaders and citizens face will further complicate the policy decisions in the near term horizon, as is well enunciated in a recent set of papers generated by Policy Horizons Canada that addresses such things as global demographic shifts, misinformation, the ability to engage Canadians amidst changes in the availability of the basics of Maslow’s hierarchy, and the many disruptions of global proportions on the near horizon (the latter demonstrated in their table below).[iii]

As has been briefed in a number of forums and identified in the recent defence policy release[iv], there are many intended improvements to military procurement and the mention of another procurement reform process that has been underway for months. For me, it is impossible to be anything but skeptical – if not cynical – based on the track record of the major players in this business: the Department of National Defence (DND), Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISEDC), the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), the Department of Finance Canada and the Department of Justice Canada (from which the contract layers in PSPC are drawn).

It strikes me that nothing short of a revolution is needed to deliver better results for the CAF, that best explained as 80% effective and as urgent as possible without delivering ineffective major weapons system platforms.

This article is too constrained to go into all of the elements needed, but some of the critical elements follow:

- A broad strategic assessment of the many significant challenges and threats to procurement on the horizon is required, as most of those articulated by Policy Horizons Canada will directly or tangentially impact procurement in terms of recruiting, retention, funding and scheduling. The traditional belief that ‘we are fine’ must be firmly rejected – insularity, blinders and numerous government agent silos working to their own drumbeat is definitely not fine in the new reality of multidimensional compounding poly-crises.

- An entirely new and self-contained department needs to be stood up to address major complex acquisition projects, taking on the responsibilities of DND, PSPC, ISEDV and TBS as a minimum. This is essential because a new culture and set of processes is required to enable the many changes required. It is also important that changes of personnel amongst the leadership be minimized for 5 years.

- The senior governance of this department should initially be comprised of very experienced people from the defence and industry business sectors. There could be a few previously retired public servants but none presently serving.

- A broad advisory committee should provide strategic and tactical advice on the changes to be tested and/or implemented. Similarly, equally skilled external mentors should be hired to provide ‘white hat’ continual assistance to project leaders and detailed reviews of projects at key decision points.

- The governance for each sector of projects (e.g. Army, Navy, Air Force, Special Forces, IT) must be tailored to include the appropriate domain knowledge provided by experienced personnel.

- Process reengineering services should be imported under contract and employing the following principle: having reviewed current procedures, nothing needs to be imported unless considered essential guidance. Immutable policies and regulations should be minimized to ensure flexibility in all activities. It is critical that commitments to time lines be in place for all activities up to contract award, and that all requirements be developed at the tactical level to be practical.

- Once projects are in contract, the employment of a strategic relationship focus supported by sustained and structured joint and integrated collaboration is essential, along with the consideration of emerging techniques for navigating complex projects.

- Regular and periodic briefs should be provided to the public in terms of organizational and acquisition projects’ progress, these not less frequently than every six months.

- Skills training for public servants and for CAF members must be provided, along with career streams developed for all CAF members and as appropriate for public servants employed within the new major defence projects organization. Furthermore, the involvement of CAF members should be strictly confined to where their input is critical as in establishing the systems operational and support requirements – they should no longer be hired to lead, as second careers or to do the jobs vacated by public servants during downsizing or as a result of civilian retirements – warriors are too valuable to Canada.

- Rigorous on-boarding must be implemented.

Many will say that this is indeed a revolutionary approach that is not required, and that the disruption to existing projects is unwarranted and self-defeating. These narratives can no longer be tolerated with the onset of ever increasing international conflicts and other disruptive threats to our way of life.

For too long, decision-makers have used our acquisition project failures as the excuse not to dramatically increase defence funding. As more and more Canadians are admitting, we are very late to need – as is now broadly understood, we cannot wait until 2040 to commission new submarines. Only a revolutionary approach will make a difference and convince our allies that we get it, that we are now moving out with change and that we will be valued contributors in the future.

Is such a revolution inevitable for the timely and effective prosecution of weapon system platform acquisitions for the CAF? It should be if we ever expect to meet our longstanding commitment to NATO’s minimal funding level.

My 48 years in the business – in uniform, as a public servant Director-General of weapon system platform projects for the Royal Canadian Navy and the Canadian Army, and as the senior Defence Attaché to the USA for four years – tell me that CAF members have the culture required and sought after internationally to make a difference. It is up to us all to give them a chance to protect our prosperity and live to tall the tale.

[i] Donna Kennedy-Glans, “Our NATO allies are despairing: Retired general says Trudeau government failing on defence”, National Post, May 12, 2024

[ii] Ian Mack, “Enhancing Defence Procurement Communications”, Policy Insights Forum, March 2024

[iii] Policy Horizons Canada Newsletter, “Futures Week 2024”, 15 May 2024

[iv] Government of Canada, “Our North, Strong and Free: A Renewed Vision for Canada’s Defence”, 8 April 2024