By Steven Fouchard

In the late 1960s, Canadian researchers working at the Defence Research Establishment in Valcartier, Quebec made a game-changing advance in laser technology with the development of a laser known as the CO2-TEA, which continues to have many industrial applications.

Today, the Canadian Army (CA) continues to take a serious look at the latest in laser technology and is finding plenty of promise. The key priorities for the CA are finding safer ways to deal with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), unexploded ordnance and unmanned threats such as drones.

Michel Szymczak, Director Science & Technology (Army) at Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), oversees the Army’s science and technology portfolio, within which new technologies are studied.

“Lasers have great potential,” said Szymczak. “Our purpose is to further our understanding of the technology, what it can do, what the benefits and limitations for military applications are and how safe they are to operate. Then we inform the army what those capabilities are and what those possibilities are.”

More specifically, DRDC is investigating potential new uses for high-energy laser (HEL) technology. As Szymczak pointed out, they have come a long way from the liquid-cooled 10-watt laser he used as a graduate student in the mid-1980s.

“It burnt paper and wood if you kept it long enough on the target. And now we’re at tens of kilowatts,” or a thousand times more powerful, he explained.

Researchers recently broke “the 100-kilowatt barrier,” he added, though the CA is working with kilowatt-class lasers.

HEL technology is widely used in the civilian world for welding work, Szymczak said.

The CA already has other laser tools in its arsenal, including range finders, target acquisition systems, and Visual Warning Technology.

“We’re working to see how we could neutralize unmanned vehicles using lasers,” Szymczak explained. “You could have an effect on the sensors and the optics by delivering that concentration of energy on the target. You could disrupt or destroy it. It’s been demonstrated by the United States that you can track and disable air platforms.”

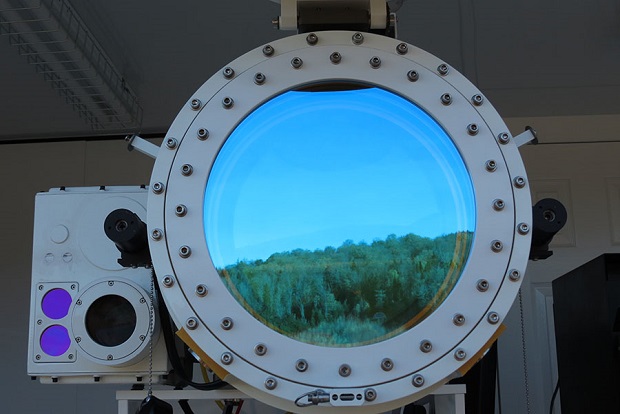

Crude but devastating IEDs took a heavy toll in Afghanistan. HEL-based devices, including two on loan to the CA from the United States, offer the promise of a much safer way to disarm, neutralize and destroy them. One has been mounted to the turret of a Cougar vehicle as a demonstrator.

The Cougar is one of three vehicles in the CA’s Expedient Route Opening Capability, which supports the detection and disposal of buried IEDs.

“What you can do is target specific components of the IED,” said Mr. Szymczak. “For example, if you see wires, you could cut the wires from a distance. The advantage is that you do it while keeping the soldiers out of harm’s way and neutralize the threat in a timely manner. The distance could be from a few metres to a few hundred metres. So it’s quite significant.”

Another aspect of upcoming research, he added, is countering the lasers that some future adversary could use against Canadian troops.

“Right now there are simple means that are being used, such as smoke as an obscurant,” Szymczak said. “There are different compositions of smoke for different threats – you hamper the propagation of the beam in the air. One day lasers will be used as a threat against us, so that’s something we have to keep in the back of our minds. We will be exposed to it sooner or later. As such, we have to consider emerging threats and ensure that the Army is not technologically surprised.”

Lt. Col.Jake Galuga, who has been observing DRDC’s work for the CA’s Directorate of Land Requirements, added that, while the technology has been proven, there is still some way to go in determining how it can best be integrated into the CA.

“It is going to take a while to figure out if and how we want to use it,” he said. “There are legal aspects to consider, there are practical aspects to consider and certainly developing any new technology takes resources.”

“High-energy lasers are not far-future items in terms of technological readiness,” he added. “The notion that this is 30, 40, 100 years down the road needs to be dispelled.”