Canada has a world-class training program to prepare future pilots for its Air Force. Becoming a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot requires a great deal of commitment and discipline, going through different flight training phases, both in the air and on the ground. It involves training in different locations across several time zones in adverse weather conditions for many hours, until eventually earning your wings. Those who have the abilities then advance to training on a range of aircraft, including the CF-188 Hornets.

Shortage of Pilots

National Defence – which includes the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and the Department of National Defence (DND) – is charged with the responsibility of protecting Canada’s sovereignty and its citizens. Part of this responsibility is defending North America and upholding international peace and stability as a participating member of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). To satisfy these commitments, the CAF needs modern equipment and a full complement of personnel.

A Canadian Press article from September 2018 pointed out that the RCAF “is contending with a shortage of around 275 pilots and needs more mechanics, sensor operators and other trained personnel as well in the face of increasing demands to conduct and support domestic and international missions.”

It is, therefore, no secret that the RCAF lacks the required number of trained pilots to meet its operational commitments. The same point was also brought out recently by the Auditor General of Canada in his 2018 Fall Reports to the Parliament of Canada, which states that “National Defence needs an effective fighter force, which means capable aircraft and personnel.” The report revealed that the RCAF had only 64 per cent of the trained CF-18 pilots during the last fiscal year. This shortage is a grave concern, not just for the CAF and Canadians but also for our Allies.

To meet its NORAD and NATO commitments simultaneously, Canada needs its full complement of aircraft and personnel to be available daily. To solve the latter, the Auditor General recommends, “National Defence should develop and implement recruitment and retention strategies for fighter force technicians and pilots that are designed to meet operational requirements and prepare for the transition to the replacement fleet.”

This is a critical inadequacy in Canada’s National Defence. So, what is Canada’s current system to produce qualified pilots? Does it have the capacity to produce more pilots? And what exactly is being done today to help fill this shortage?

Two Training Schools

Qualifying as a trained RCAF pilot, a student must undergo training at two different training schools in Canada: 2 Canadian Forces Flying Training School (2CFFTS) and 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School (3CFFTS). Independent contractors from the defence industry operate the facilities and services at these two schools.

The NFTC Program

At 2CFFTS at 15 Wing, CFB Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan and 4 Wing, CFB Cold Lake in Alberta, the training program is a collaborative endeavour between the RCAF and a leading training and simulation contractor, CAE Inc. Originated back in 2000 as a 21-year contract between the Government of Canada and Bombardier Aerospace Military Aviation Training (BA MAT), the NATO Flying Training in Canada (NFTC) program was designed to provide Basic Flying Training (BFT), advanced jet, and Fighter Lead-In Training (FLIT) for future fighter pilots for the RCAF.

In October 2015, CAE acquired BA MAT’s business for almost $20 million and became the prime contractor for the NFTC program. Scheduled to expire in 2021, the program was extended in January 2017 for an additional two years and will now run until at least 2023, with a one-year option to extend the contract through to 2024.

Speaking about the announcement at the time of the extension, LGen Mike Hood, who was then commander of the RCAF, said: “The NFTC program delivers world-class pilot training to Canada and participating allied nations. In modifying the operating period of this NTFC contract, we will ensure that this essential pilot training system continues until a new program is up and running.”

Joe Armstrong, Vice President and General Manager of CAE Canada, said the acquisition of NFTC is not only a great asset for them in Canada, but it has opened up possibilities to export their capabilities and training expertise internationally. That is evident in the U.S. Army Fixed-Wing training program for which CAE has been contracted to conduct comprehensive initial and recurrent training for more than 600 U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force fixed-wing pilots annually. “This is a comprehensive pilot training program, including live flight training, of which a lot is based off the NFTC as well as the live training operations that we’ve been running for quite a long time in civil aviation,” said Armstrong.

He went on to explain that delivering a training outcome for a specific training objective is about training people to be more effective, better at their job, and safer in their environment. The company sees this from the perspective of integrating every possible media asset into the delivery of that training solution or service. Having access to the full breadth of possible media assets – for example, courseware, simulators, live instructors, classrooms, and aircraft – CAE, in collaboration with DND is effectively working “to produce an overall training effect through a training service program.”

As the prime contractor of the NFTC, CAE is responsible for all support aspects at the school and providing the CT-156 Harvard II turboprop and CT-155 Hawk advanced jet trainer, which are leased from the Government of Canada, but maintained and serviced by CAE. The academic and simulator instruction is delivered by CAE employees who have previous military flying instruction experience. The company also operates the multi-purpose facility at this location, which houses offices, classrooms, briefing rooms, three Harvard II simulators and a Hawk simulator.

DND provides the students, live flying instructors, airspace, syllabus for the ground-based training and flight training, air traffic control personnel, flight safety program and training standards for the NFTC program.

In addition to training RCAF pilots, the NFTC program is also available to other NATO partners and Allies through direct government-to-government agreements. To date, students from Denmark, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Italy, Hungary, Austria, and the United Arab Emirates have participated in the program.

The CFTS Program

The other school, 3CFFTS, is in Portage La Prairie, Manitoba and is operated by KF Aerospace through the Contracted Flying Training and Support (CFTS) program. The CFTS program is a flying training and support services contract for the Primary and Basic Flying Training and Multi-Engine and Helicopter pilot training programs. These sessions are conducted at the Southport Aerospace Centre (SAC), which was formerly known as Canadian Forces Base, Portage-La-Prairie, Manitoba.

In 2005, the CFTS contract was awarded to Allied Wings, led by KF Aerospace, and included Canadian Helicopters, Atlantis Systems Intl, Black & Macdonald, and Coastal Pacific Aviation. Under the 22-year, $1.77B contract, Allied Wings is responsible for providing the Grob G120A aircraft for Primary and Basic Flying Training, the Raytheon King Air C90B for Advanced Multi-Engine Flying Training, and converting the Bell 206 Jet Ranger and Bell 412 Griffon helicopters from Canadian Forces inventory for Advanced Helicopter Flying Training.

3CFFTS conducts the flight training while the contractor is responsible for all other aspects of training and support services, including infrastructure, aircraft, accommodation, meals, academic training, simulator training, and air traffic control.

The program includes full-motion flight simulators to support the Multi-Engine and Helicopter Flying Training programs. To facilitate the necessary training to carry out this contract, a new 80,000 square foot training facility was constructed at Southport, which includes high-tech classrooms, student lounges, briefing rooms, boardrooms, a 150-seat theatre, a flight planning centre, fitness centre, reference library and ceremonies hall. This complex also houses simulators and devices for flight training. Training through this contract began in 2006 and will run until 2027.

Different Phases, Different Pilots

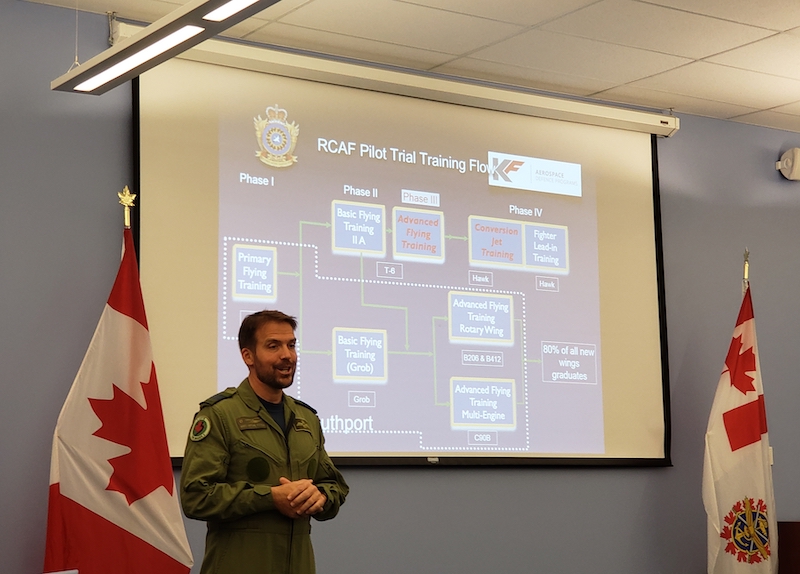

Students go through different phases of training before qualifying as pilots for the RCAF. These phases are tailored to produce pilots to fly on different platforms, namely helicopters, multi-engine and fighters. A combination of training at both schools provides the foundation for students in their careers as future pilots for the RCAF.

Phase I of training begins at 3CFFTS in Portage La Prairie where all students go through the Primary Flying Training, with the exception of those with a Commercial Pilot’s License and over 100 hours flying time, who go on directly to Phase IIA. Phase I includes three weeks of ground school, 14 flying missions totaling 14.7 air hours, and six hours on Flight Training Devices (FTDs).

During Phase I, students fly their first training missions on the Grob G120A, a twin-seat, piston engine aircraft. It is at this level that basic pilot skills are assessed, which helps to refine the selection process for who moves on to Phases II and III.

LCol Marc-Antoine Fecteau, Commandant of 3CFFTS, explained that the decision of filtering out those candidates who are not likely to achieve the required pilot training standard within the allotted training time is made during this first stage. It is a decision, though, that is not made lightly. The Commandant and his team work to ensure that all areas are covered for that student.

“A review is conducted at different levels to ensure that we didn’t make a mistake,” said LCol Fecteau. “We want to ensure that there was nothing on the outside that could change the student’s performance, like, for example, a medical emergency of a close family member.” After considering all the factors, the final decision is made by the Commandant.

The early detection of someone unlikely to succeed in the pilot training program is critical because of the substantial investment. The cost to train a pilot years ago was around $1.5 million, but today, that cost is nearly doubled at $3 million according to LCol Fecteau.

The initial stage has a capacity to accommodate up to 155 students. Phase II is divided into two groups, with capacity for up to 128 at the Basic Flying Training IIA at 2CFFTS in Moose Jaw on the CT-156 Harvard II turboprop, and an option for 10 to remain at 3CFFTS for Basic Flying Training on the Grob. The training on the Grob during this phase equips students on advanced clearhood, instrument flying, formation, navigation and night flying. The syllabus covers 66 air hours and 28 hours on FTDs.

For Phase III, approximately 90 from the Basic Flying Training IIA at 2CFFTS in Moose Jaw will go back to 3CFFTS in Portage La Prairie to train on the Advanced Flying Multi-Engine with the C90B King Air and the Advanced Flying Training Rotary Wing on the B206 Jet Ranger and B412CF Outlaw helicopters. Students for Multi-Engine will complete 39.5 air hours and 55 FTD hours. Those in the helicopter stream will spend 53 air hours in the B206 and 40 air hours and 54 FTD on the B412.

Approximately 30 of the students from Phase II will remain in Moose Jaw and continue training on the Harvard during Phase III Advanced Flying Training. At the end of the third phase, all successful pilots from both schools are awarded their flying badges or wings. At this point, after about two years of rigorous training, approximately 70 to 80 percent of the graduates will reach the end of their training and go on to fly either a multi-engine or rotary wing aircraft.

The remaining 20 per cent that started Phase III on the Harvard in Advanced Flying Training will be destined for fighters and will then go on to Phase IV to begin training on the CT-155 Hawk, a Rolls-Royce turbofan engine advanced jet trainer in Moose Jaw. During the second half of this phase, students are transferred to 419 Tactical Fighter (Training) Squadron at 4 Wing, Cold Lake, Alberta to participate in the Fighter Lead-In Training (FLIT) course which focuses on tactical flying training on the Hawk.

For those going on to fighter training, LCol Scott Greenough (Ret’d), a former Commandant of 2CFFTS and CAE’s Program Manager of NFTC, explained the speed progression and the complexity of the training. Students first start out flying at a speed of two miles a minute in the Grob, then four miles a minute in the Harvard with a corresponding increase in tasks and complexity. By the time they move on to the Hawk, they are flying at eight miles a minute. Flying at this speed, students still have to keep an eye on the display, operate switches, and control the throttle and stick. “We are making the world go by faster and at the same time training the brain to operate at such a speed to take a whole lot of information in and process it quickly,” said LCol Greenough (Ret’d). “That’s really the skill set required of a modern-day fighter pilot.”

After graduating from NFTC, the new batch of fighter pilots will then join their first CF-188 Hornet squadron.

Filling the Shortage

Canada has an internal focus to fix the current shortage plaguing the RCAF. “There is a shortage of pilots in the world, and every country is looking at good ways to train their pilots, that includes training somewhere else,” said LCol Fecteau. He went on to add that many would prefer that somewhere else to be Canada, but since we are trying to fix our shortage problem the training system is running at “full capacity.”

Peter Fedak, Site Manager responsible for the CFTS program in Southport, explained that “full capacity” does not relate to the simulators or facilities but mainly to instructors. “The key part is instructors, and as the RCAF tries to maintain operational tempo and feed the schools, we are trying to tap and find instructors to train pilots,” said Fedak.

The decisions being made today though will not yield results for the next few years. Fedak explained that ramping up today will produce qualified pilots in about three to four years, in the best-case scenario, and up to seven years if the student does not have a degree. “The impact of decisions made now will be felt in six or seven years,” said Fedak. “This is a condition that neither the school nor industry can control. It is a long process for the long term.”

Training

Through the CFTS program in Portage La Prairie, KF Aerospace is required to do a training event per day, per student, whether its flight, ground school or simulation. The flight schedule is created the day before with the RCAF to ensure that the required aircraft is available for training. KF Aerospace has a 100 per cent availability of aircraft ready for training.

“If we have 22 B412CF Outlaw flights that needed to be completed in one day, we can do that with six machines, flying four times. That will leave us with three spares. If an aircraft breaks down then we bring a spare one in and within 30 minutes we are good to go again,” explained Fedak. Having such a rigorous schedule and spare aircraft keeps downtime to a minimum.

At the 3 CFFTS school, students go through training from basic to advanced using desktop trainers, procedural trainers, touchscreen to Level 5 trainers, whether it’s cockpit procedures trainers or devices with visuals. The newest addition to the course is the Jet Ranger Trainer for the Bell B206. In this Level 7 FTD, the cockpit moves up to six inches to provide the motion of flying while the screen remains stationary. “This is a very unique device and the most realistic helicopter trainer I’ve ever been in,” said Fedak. He went on to point out that even with the advancement of technology, there is no such thing as a replicator. The aircraft is the only machine that can replicate exactly what happens in flight, but it’s the “closest thing – a real evolution to the point that Transport Canada and the FAA don’t know what to call it.”

Fedak stressed that this is a military program that they support. “We do all the support for them with the oversight of their contract authority, and it’s all under their quality assurance, whether it is standardization, flight standards, or programs. It’s all 100 per cent RCAF’s.”

For its training in Moose Jaw and Cold Lake, CAE operates 22 Harvards and 17 Hawks. After about 400 hours of flying, each aircraft comes in for a 15-day major maintenance activity managed by over a hundred CAE technicians. With that maintenance schedule, both fleets have a 90 per cent availability for flight training.

Innovative Ways of Training Pilots

The two flying schools utilize six fleets of aircraft – consisting of the Grob, Harvard, King Air, Bell 206, Bell 412 and the Hawk – for training. “We conduct about 34,000 hours of flight training across the two locations, and the result is typically about 100-115 trained pilots per year,” said Col Denis O’Reilly, Commander, 15 Wing Moose Jaw and Military Director of NFTC.

In 2016, the schools graduated 116 pilots, 115 in 2017, and last year was down to 107. Col O’Reilly pointed out that the drop in 2018 is intentional because of the success in the previous years. “We did so well that we’re stacking them up a little bit, we’ve got to let the operational training catch up,” he said. “We are trying to achieve a balance and shift the resources away from our initial pilot training to wings.”

He explained that the increase in output is not due to more significant financial investment, but by being innovative. One such way is instructor training development. Previously, instructors were trained to teach the entire syllabus. The last time an instructor may have flown a Harvard was as a student. To get up to speed, they would have to be retrained to a level where they can teach the entire syllabus.

“That is a bit of a wasted effort at the very beginning when they’re not familiar with the aircraft,” said Col O’Reilly. Instead, the decision was made to have the instructors teach the basic parts of the syllabus for the first six months to a year. After that, they fly with other senior instructors to learn the advanced syllabus so that they can be fully equipped to teach it. This resulted in savings, and the schools managed to get instructors to the line twice as fast while spending fewer resources later on.

Another way is using block training syllabus. The general concept of training is linear learning, but with block training, it is about taking an entire “chunk” of lessons and measuring performance to get the students to the end of the block at the right level. “The result of that has been very positive in the sense that we’ve reduced our extra tools and extra training in half. We’re not wasting time retraining people because they cannot learn on a certain rate,” said Col O’Reilly. This change produced a decrease in attrition rate and, at the same time, increased student confidence. Block training provided a more focused use of flying hours with the students given the opportunity to map their trip planning and focus on weak areas rather than going through a very prescriptive training plan.

Through these types of innovative changes, the schools were able to produce more pilots, even though “the overall training system hasn’t changed, regarding the number of resources and aircraft,” said Col O’Reilly.

Ramping Up

At the end of July 2018, the RCAF was short 275 pilots. To fill this deficit, increasing the input of students and increasing the output of trained pilots would be the obvious answer. But to get there requires a coordinated effort with the operational community. “We will only intentionally ramp up here when they are ready to receive them,” said Col O’Reilly.

Canada, as well as other countries in the world, is plagued by the lack of sufficient pilots to meet the growing demands of military operations. Even though the situation seems grave at the moment, with a world-class training system in place, Canada is in position to continue producing world-class pilots to meet the needs of national and international obligations. By implementing more innovative methods of training and incorporating lessons from the NFTC and CFTS programs, Canada most assuredly has the experience, capability and capacity to produce more pilots to fill the complement required to protect Canada’s sovereignty and citizens.

The future success of this world-class system is dependent on having enough suitably qualified young men and women to fill these programs. So how does the future look? According to Col O’Reilly: “In the last six or seven years that I have been involved, we’ve had no shortage of interest from people who want to be pilots.” Despite the current deficiencies, Canada is on the right track to a fully-staffed RCAF and the ability to fulfill all of its defence obligations both at home and abroad.