Trump’s Trade war will force country of origin tracking in supply chains.

I wrote an article in the Toronto SUN newspaper a few months ago titled, “How America won the chicken war and why Trump will try it again”. The crux of the article was about a tax that the Germans imposed on American chicken after the Second World War. I recounted that at the time, prosperity was working its magic, allowing Europeans to live cheaper and increase their standards of living, which was helping to rebuild their shattered economies.

The Chicken Tax

Germans, in particular, were enjoying their cheap American frozen chicken day in and day out, much to the annoyance of the small, struggling German chicken farmers. As a result, in a purely political reaction, West Germany imposed punishing duties on chicken imports.

Meanwhile, Americans had become hooked on the lovable Volkswagen beetle, as well as the iconic VW “hippy van,” which had exploded in sales. Pickup trucks were very clearly Volkswagen’s next market opportunity. American auto manufacturers, however, much like their German chicken farming counterparts, weren’t keen on competing with cheap imports. Needing the auto manufacturers’ union support, President Johnson made a deal with the United Auto Workers in 1964 and responded with his retaliatory 25 per cent tariff against the Volkswagen imports. It was referred to as the “Chicken Tax,” which still exists to this day, and applies to all countries outside NAFTA.

In politics, it’s almost always “tit for tat” when protectionism starts. Not all wars have a clear winner, but it would seem today that Americans dominate in pickup trucks much more so than Germans do in chickens. The Chicken Tax essentially legislated American success in the light truck market, and now President Trump is hoping to recreate this same sort of success in other markets.

Trump’s Chicken War

The United States is the largest consumer market in the world. To a businessman like Trump, who prides himself on his ability to “negotiate,” the obvious solution is to tilt the playing field in his direction, and simply legislate the jobs. For example, TransCanada Pipelines had proposed that 50 per cent of the Keystone pipeline would be built using U.S. steel, however, President Trump’s executive order demanded 90 per cent to be made in the U.S.

Although he seems to have relented on the steel specifically, given that it was mostly already stockpiled, Trump has started his “chicken war”. But what does this mean for the defence sector, especially given that it is typically exempt from WTO or NAFTA agreements? And how will other sectors be impacted?

The Jones Act

To some extent, there are already a number of areas and industries in the U.S. where this reporting is already required – particularly in the transportation and defence sectors. For example, the Jones Act requires that a vessel must be built in the U.S. if cargo is being shipped from an American port to another American port, either directly or through a foreign port.

The Jones Act is covered under Section 27 of The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 and requires that vessels be constructed or rebuilt in the U.S., owned by citizens of the U.S. and crewed by U.S. citizens and permanent residents. Further, the Berry Amendment requires that the United States DOD give preference to American suppliers on certain products, including textiles and metals. Not to be confused with each other, both the Buy America and Buy American acts further require preference be given to American companies when the Federal government is the client. Though only applicable right now to federal procurements, the type of tracking required by these programs is something we see being flowed down onto industry – to prove they are doing the maximum in their efforts to support American enterprises.

Country of Origin

Practically speaking, I now believe that Trump’s focus will be requiring data on the “country of origin” content in supply chains. In other words, to foreign companies working in and selling to America – the requirement to track where their suppliers are throughout their supply chains – and to local American based businesses – well, the exact same. So, to all business leaders who touch the American “elephant” in any way, I believe the question of the near future will be: “Do you know where your suppliers are – and how about your suppliers’ suppliers?”

Large Corporations and Local Supply

A lot of work outside of managing this content for defence offsets at OMX has been around helping large corporations in other sectors source locally and track/report on the impacts, because it is “nice to have” or just the right thing to do. Recognizing this connection between local supply chain and their success, the CEO of Suncor, Steve Williams said, “Businesses and economies are at risk if we fail to meet society’s rising expectations for our performance”.

I believe that with shifting geopolitical attitudes towards “bringing jobs home,” “reshoring” or just “buying local,” the light is going to be shone there more formally. In March, I met with Scott N. Paul, the President of the Alliance for American Manufacturing and an Advisor to Trump on Trade at supply chain conference in the United States. For this article, he clarified: “I expect the Trump Administration to pursue an array of policies designed to restore supply chains and encourage domestic content in public procurement. So far, much of this guidance has been rhetorical in nature, but look for policies to emerge soon.” Scott Paul has also commented publicly that we can no longer assume the World Trade Organization is all that matters.

I also spoke to Robert Baines, the President & CEO of a board that I sit on: the Canadian NATO Association. Robert forecasted that “President Trump could conceivably implement a favoured supplier scheme whereby American defence firms would be directed to only seek procurement contracts from countries fulfilling the 2 per cent promise, or that countries could only receive access to procurement opportunities pro-rated to how much they contribute.” Baines went on to add, “While it would be a nightmare for NATO industrial defence collaboration, it would enable the United States to react to the NATO member defence budget deficit on a bilateral basis with each individual NATO member and would add an incentive for countries to increase defence spending in order to save industry jobs.”

You can also expect more scrutiny to be placed on labels such as “Crafted in America” or “Assembled” in America, where significant portions of the manufacturing process are still done offshore, shipped to the U.S. and then assembled. The emphasis will be on proving how much of the work was actually done in America by American citizens.

Harmonized Tariff Codes

I remember when I was running my factory in the Dominican Republic, we were importing raw materials from China into our Free Trade Zone, converting the materials into final products, and, under the new Harmonized tariff codes, were able to ship them to the United States and pay that relevant tax. If a product changes its tariff code, it then becomes that country’s content.

For instance, a Honda engine block cast in Japan is not an engine. It is a casting. When all the parts are bolted on in the United States, it becomes an American-built engine. I have a feeling the World Customs Organization (WCO), that classifies traded products, will need to be involved. Here, the more you can back up with hard data, the more legitimate your claim to being “Made in America” will be, and that is where your supply chain and procurement efforts will come into play. Looking at how the Canadian offset program calculates Canadian Content could be a good place to start. Based on our understanding of Canada’s sophistication, we have built electronic calculators throughout OMX for measuring domestic content around the world.

Local Sourcing

I recently spent a week at the SAPAribaLIVE conference where the CEO of SAP, Bill McDermott, spoke. As the leader of one of the world’s largest software companies selling to the world’s largest corporations, it was interesting to see how much of his focus has shifted to understanding the social impacts of supply chains. We’ve since signed a partnership with SAPAriba, which is the division of SAP focused on B2B supply chain. They have up to a million opportunities within their platform at one time, which will be continuously filtered and sent out to suppliers in the OMX network starting in May 2017.

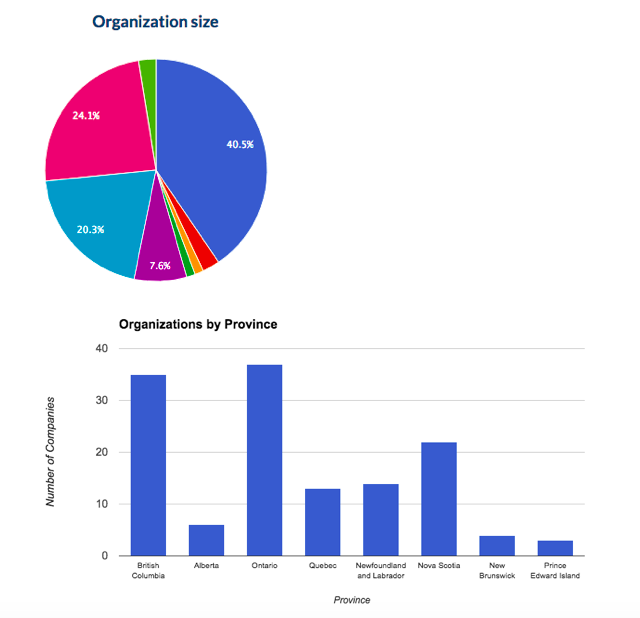

Companies already using SAP Ariba for procurement will now also get the added benefits of regular OMX users who are tracking and reporting on their local spending through OMX’s tracking and supplier management tools. Below are some screenshots of the data analytics OMX generates in local content.

So, as you can see, sourcing locally is getting serious, and so are we.