It started out as the “European Collaborative Fighter” (ECF) program which consisted of British Aerospace (BAE) and Germany’s Messerschmitt-Bolkow-Blohm (MBB) in 1979. Later that year, the initiative was joined by Dassault from France which saw the program designation changed to the European Combat Aircraft (ECA).

Like most joint design processes, there were disagreements and the ECA was no exception. While each of the partners were working on their own individual concepts, Dassault and British Aerospace reached an impasse with regards to the engine. Dassault wanted the SNECMA M88 powerplant as it would help keep jobs back home in France, and British Aerospace wanted to make use of a modified Rolls Royce RB-199 powerplant for much the same reason. This led to Dassault’s departure from the project in 1981.

The Eurofighter went through several changes in the early 80’s and went through many of the pains that 1980’s-era designs went through, especially post-Cold War when many programs were put under the microscope. The project survived, and the Eurofighter 2000 eventually became the Eurofighter Typhoon.

The “European Aeronautic Defense and Space” company (EADS) changed its designation to Airbus Defence and Space and is headquartered in Germany, which is why Airbus comes up with relation to the Eurofighter and many people scratch their heads looking for Germany and Spain in the ownership structure. The final structure broke down as 46% Airbus Defence and Space company (Germany/Spain); 33% BAE Systems (the UK), and 21% Alenia Aermacchi (Italy).

The initial Eurofighter Typhoon found its way to Germany and Spain in 2003, Italy in 2005 and the UK in 2007. The Typhoon was declared fully operational as a multi-role fighter on July 1, 2008.

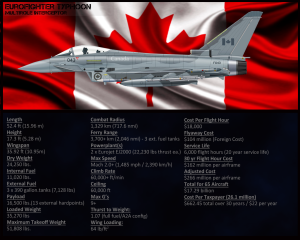

As you can see pretty clearly from the graphic above, the Typhoon is very far from being a low-cost acquisition. No fighter jet is, but the Typhoon is a fair bit more expensive than the Super Hornet, a lot more expensive than the Gripen NG — but still half the cost of the F-35.

The Typhoon is made from advanced composite materials. 70% Carbon Fibre composites, 15% Aluminum Lithium Aluminum Casting and Titanium combined, 12% Glass Reinforced Plastics and 3% “Other”.

The high-tech materials, of course, make the Typhoon lighter which increases its maneuverability, but it also reduces radar signature, improves range and performance. It’s also what helped to make the Typhoon unstable to drastically increase its maneuverability in aerial encounters. This is offset by advanced computers which literally keep it in the air and under control. It’s also capable of sustained turns in excess of 9 G’s, the only limit — like most high G fighter aircraft — is the pilot.

The Typhoon has had its share of troubles lately, however. Cracks were found in the airframes at just under 4,000 hours despite the claimed service life of 6,000 hours. This poses a problem, as like the US Navy with the Hornets, the UK has plans to push the service life of its current fleet of Typhoons to 2030 when it’s expected the F-35’s will have fully taken over. That would mean a service life of around 9,000 hours if they can rectify the structural issues, which would bode well for Canada.

Let’s also not forget that as far as building and innovating, Bombardier has just recently built the CS100 and CS300 using primarily composite materials. Given that Eurofighter originally offered final assembly in Canada as well as full tech sharing and the license to modify the design, this could also allow Bombardier to manufacture the Typhoon and both create and reverse engineer technology.

BAE Systems presented a mock-up in 2011 of a carrier variant of the Eurofighter that would make use of thrust vectoring tied into the pilots’ flight control system. This would also regulate the positioning of the nozzles and would allow the pilot to focus on controlling the aircraft. Thrust vectoring would make the already impressive maneuverability of the Typhoon that much more stellar. The reinforcements to the airframe would no doubt also help to further improve the reliability of the structure.

While on the subject of reliability, the Eurojet EJ2000 engines are not only plenty powerful, they are extremely reliable and durable much like the F404 engines in our current CF-18’s. The Eurofighter is also primarily an interceptor and as such, it is a perfect fit for Canada’s primary needs with regards to daily Arctic patrols, OCA and DCA roles and NORAD. It also has adequate payload in air-to-air and air-to-ground applications and is completely integrated with NATO.

What sets the Eurofighter apart from the Hornet, with regards to armament, is its ability to carry the forthcoming Meteor BVRAAM. This particular missile uses Ramjet technology and advanced sensors that allow for excellent maneuverability and superb range. The sensors use a combination of frequently updated data to regulate the use of the propulsion system and change course as required. It doesn’t have an AESA radar at present, but one is in the works. The sensor fusion and IRST systems are all on-par with the Super Hornet and more than capable of handling any threat to Canada now and into the future.

The only real sticking point for me is the structural issue. Aside from that, it’s fast, it has excellent thrust-to-weight, it has good range, it’s receptive to upgrades and it’s cavernous nose section leaves plenty of space for future radar tech. Furthermore, the economic benefits attached to the Eurofighter offer just makes the package that much more appealing.